Hélène Schernberg, Director Public Policy & Regulation

Munich Re.

Geneva Association. 2026.

Addressing Growing Protection Gaps through Better Public-Private

Insurance Programmes.

Author: Hélène Schernberg. February.

Hélène Schernberg, Director Public Policy & Regulation

The disaster protection gap – the uninsured share of economic losses from natural and man-made disasters – is widening. Between 1980 and 2024, natural catastrophes caused an estimated USD 6.9 trillion in property losses, of which two-thirds were uninsured.1 Uninsured losses impede economic growth and push governments into slow, unpredictable, and budget-destabilising post-disaster relief.2

Investing in risk reduction – measures that prevent or mitigate losses and support recovery and adaptation – is often more cost-effective than rebuilding. In addition, insurance can spread remaining losses and provide rapid, pre-arranged liquidity that keeps firms open, preserves jobs, and reduces the need for ex-post fiscal support.

In some regions and for some perils, however, private market mechanisms do not generate enough risk reduction or insurance coverage. Government intervention can help narrow the disaster protection gap to an efficient and socially acceptable level.

Three market frictions drive the gap:

A. Increased losses: Climate change and technological progress intensify hazards while urban concentration and digitalisation increase exposure. Ageing infrastructure, weak building codes, and insufficient investment in risk reduction increase vulnerability.

B. Insufficient demand: Individuals underestimate the likelihood of rare events or expect government relief, reducing the perceived need for insurance. For low-income groups, premiums can be prohibitively expensive. Moreover, factors like financial-literacy levels impact demand.

C. Supply uncertainties: Highly correlated losses and significant uncertainty or ambiguity increase regulatory capital requirements, forcing insurers to charge higher premiums or to withdraw coverage. Inflation and price regulation further erode profitability and availability.

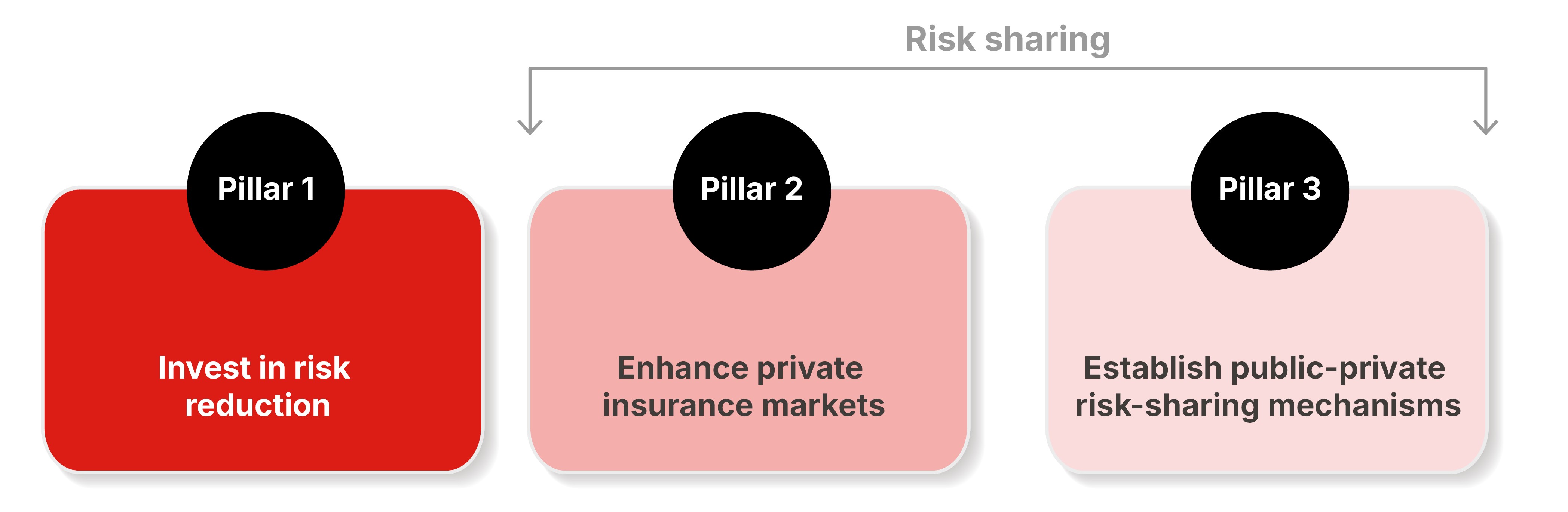

This report proposes a proactive, three-pillar strategy to narrow disaster protection gaps:3

Figure 1: A proactive strategy with governments relying on three pillars to reduce and share risks

Source: Geneva Association, adapted from Zurich Insurance Group

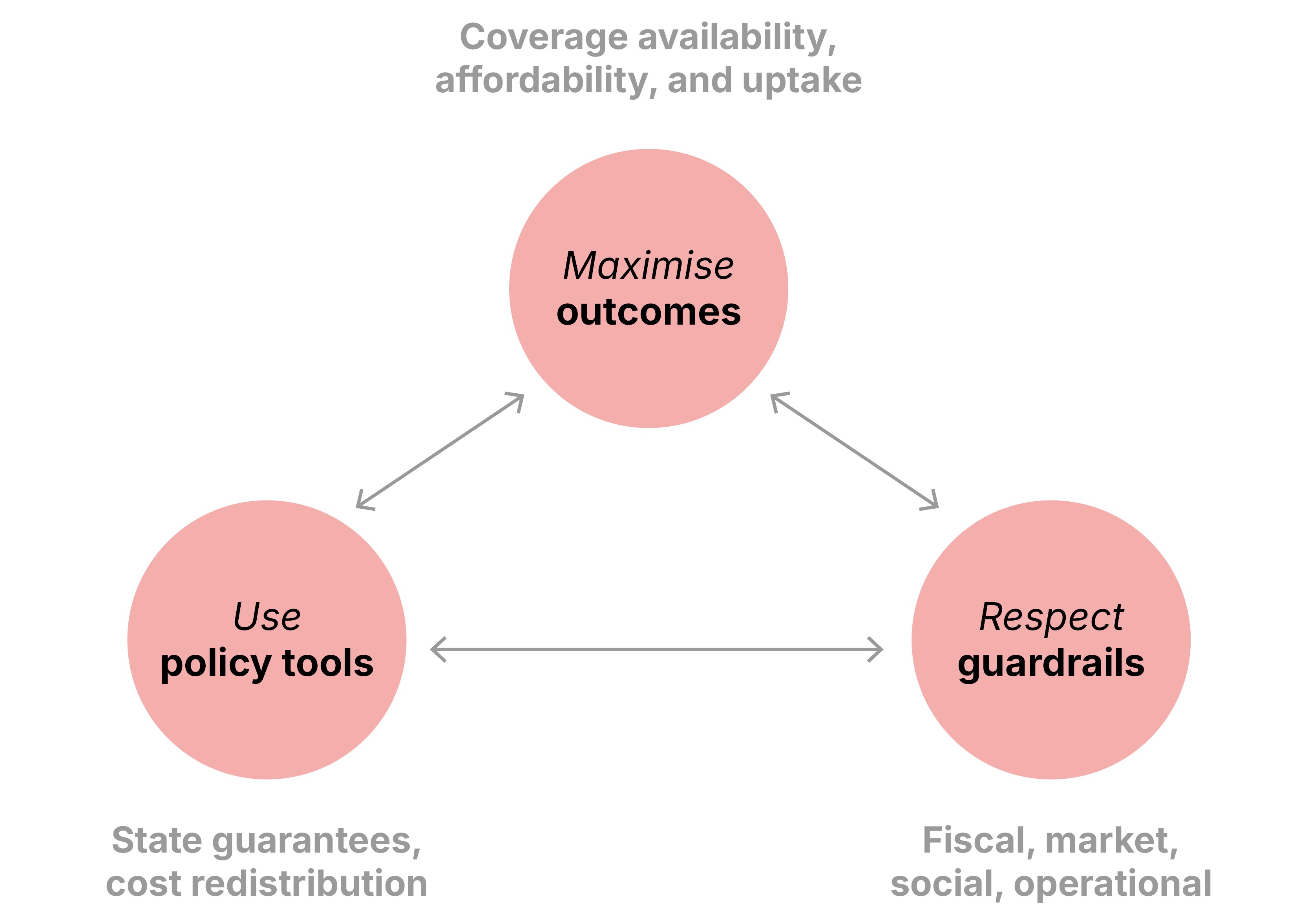

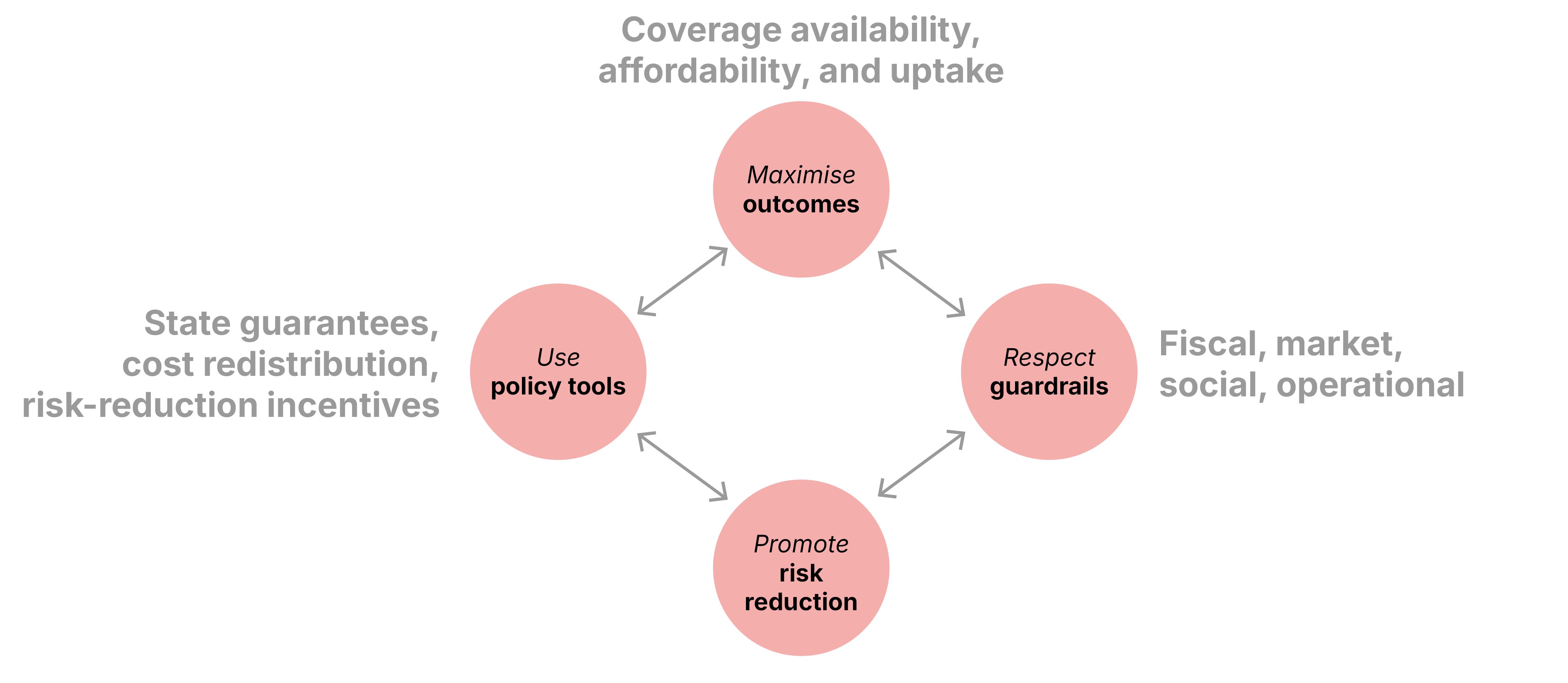

A PPIP aims to improve three outcomes: coverage availability, affordability, and uptake. Policymakers rely on two main tools: state guarantees to boost supply (availability); and cost redistribution – including insurance mandates and solidarity pricing – to support demand (affordability/uptake). Four guardrails constrain how policymakers use these tools:

The policy tools may stretch one or more guardrails, potentially requiring complex policy trade-offs. Strengthening the social guardrail though solidarity pricing improves affordability and uptake but can dampen risk signals, challenging the market guardrail. Over time, unmitigated risks might stress the fiscal guardrail. Likewise, state guarantees can crowd out private re/insurers, stifling the innovation and competition intended by the market guardrail.

Figure 2: Designing a PPIP is an optimisation problem

Source: Geneva Association

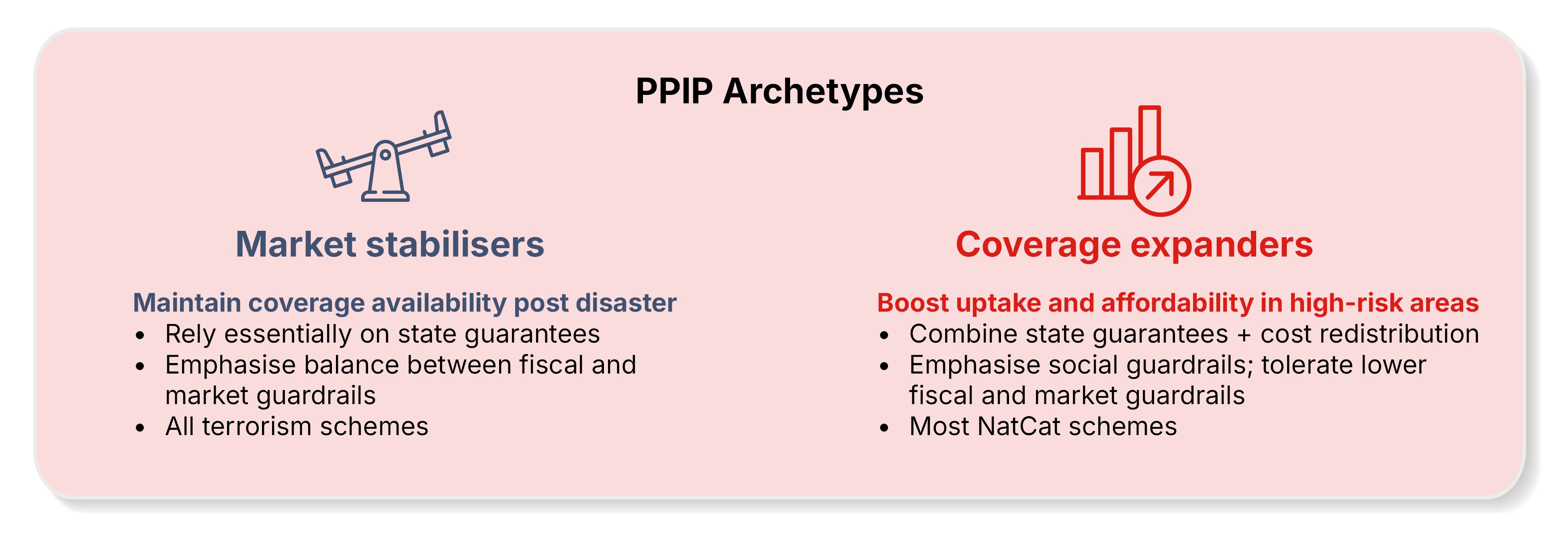

This report analyses 14 existing PPIPs across natural and man-made perils (terrorism). They balance policy trade-offs in two archetypal ways:

While market stabilisers provide coverage availability and price stability, they depend on voluntary participation and risk-based pricing. Significant protection gaps can remain: for example, just 4% of UK small businesses have terrorism coverage.4 Additionally, some PPIPs do not address contemporary risks, such as cyber threats or intangible asset losses.

Coverage expanders, combining mandatory participation with solidarity pricing, can reach uptake of 90–95%, such as in France and Spain. Voluntary programmes are less successful, as evidenced by opt-out rates from the US National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).5

Many PPIPs stretch one or more guardrails. Some experience severe fiscal strain, including fund depletion at France’s CCR after recent droughts, the US NFIP’s enormous debt burden, and New Zealand’s Natural Hazard Commission (NHC) following multiple earthquakes. Market distortions arise when the PPIP crowds out private capacity, as in France. Flat rates can favour wealthier households in exposed regions, while risk-based pricing proposals in the NFIP (US) have triggered political backlash. Some schemes have faced high operational loss ratios, as recently seen in Australia’s Cyclone Reinsurance Pool.

Pillar 3 (PPIP) interventions frequently precede or replace Pillar 1 (risk reduction) strategies. Flood Re (UK) is accused of allowing the government to defer flood prevention measures, while US NFIP flood insurance subsidies have encouraged population growth in high-risk areas.

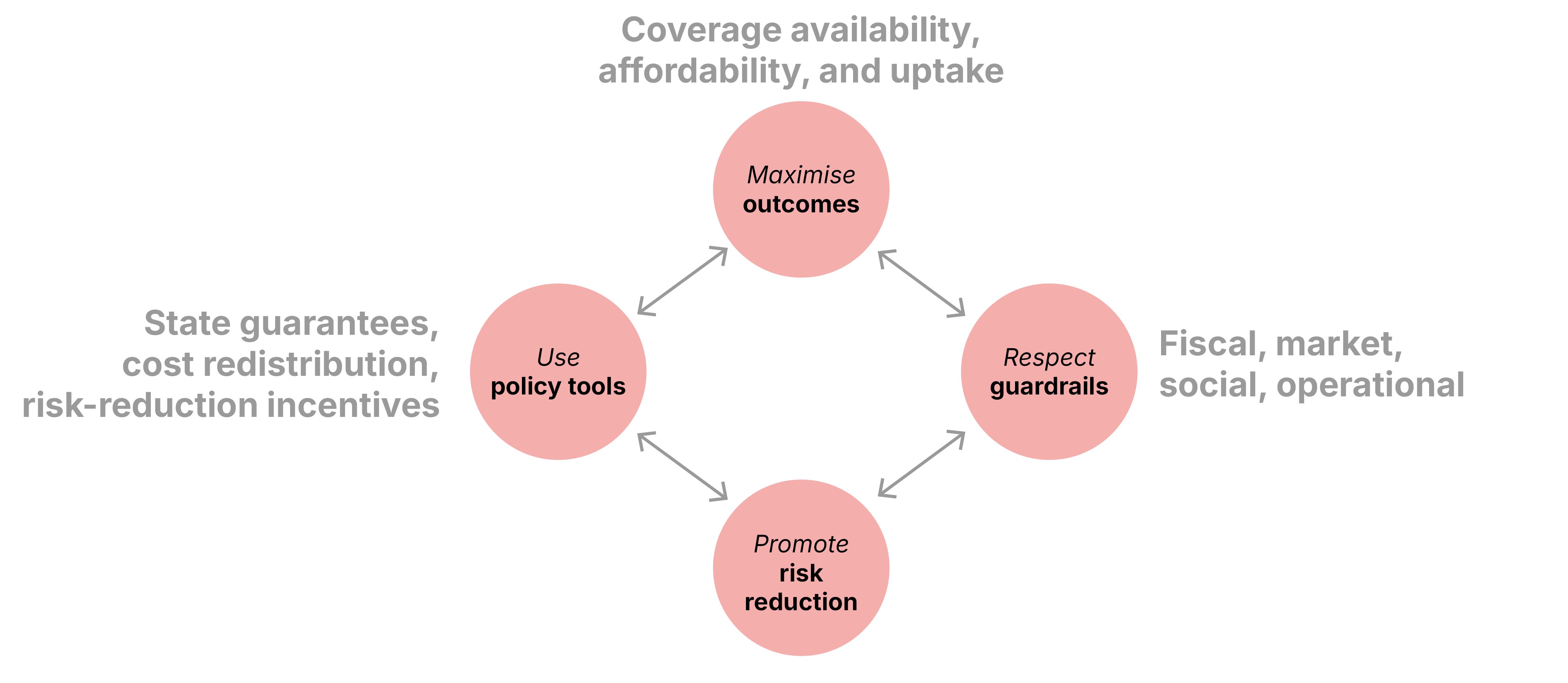

Policymakers should view PPIPs as part of a broader resilience strategy rather than as isolated financial mechanisms. PPIPs should not only share post-disaster losses but also support – not undermine – public and private efforts to reduce exposure and vulnerability. While a PPIP can incentivise individual behaviour, government actions, such as infrastructure investment, have the greatest risk-reduction benefits, emphasising the need for government dialogue with the PPIP.

Figure 3: PPIPs must not only maximise coverage outcomes (Pillar 3) but also ensure that the PPIP’s design promotes individual a

Source: Geneva Association

PPIPs are costly and complex. A four-step process can assess the need for and potential role of a PPIP:

Several key principles provide scope for designing or reforming PPIPs to remain within fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails and contribute to resilience. These principles relate to:

Applying this framework to two emerging risks – for which calls for PPIPs are growing – reveals important considerations:

PPIPs are often essential tools for maintaining insurability of disaster risks, with their design and operations as part of a proactive risk-management strategy. Governments must lead on risk reduction. PPIPs should be (re)designed to complement and incentivise risk reduction rather than subsidise exposure. Progress depends on aligning incentives around the common goal of proactively building a resilient society.

In recent decades, societies have grown more prosperous, more interconnected, and, paradoxically, more vulnerable. Natural and man-made disasters now unfold against a backdrop of dense economic activity, stretched public finances, and rising expectations of protection. In this environment, insurance is a cornerstone of resilience, helping households, businesses, and governments absorb shocks and recover more quickly. Yet the frequency, scale, and sometimes systemic nature of today’s risks – and urgent need to address insurance availability and affordability challenges – are testing the limits of existing mechanisms and forcing a reassessment of how risk is reduced, shared, and ultimately borne.

This report examines widening protection gaps, and the role that public-private insurance programmes (PPIPs) can play in addressing them. Our comparative analysis of 14 programmes across countries and perils shows that many PPIPs have succeeded in restoring or increasing coverage where private markets alone could not. However, too frequently, they have functioned as passive shock absorbers rather than as part of a broader strategy to reduce risk. The analysis highlights the fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails within which PPIPs must operate, and documents how pressures on these guardrails are mounting as risks grow and losses accumulate.

Maximising protection for society over time requires a shift from financing disasters to proactively managing risk. Governments must prioritise investment in risk reduction, strengthen private insurance markets, and deploy PPIPs strategically where private capacity is missing, rather than viewing them as substitutes for prevention. PPIPs, when well designed and aligned with national resilience strategies, can do more than share losses after disasters: they can reinforce incentives to reduce risk, protect public finances, and support faster, fairer recoveries. The recommendations set out here aim to support policymakers in making that transition, at a moment when the growing cost of inaction is becoming ever clearer.

Jad Ariss

Managing Director

The disaster protection gap – the uninsured share of economic losses from natural and man-made disasters – is widening. Global natural catastrophe (Nat Cat) losses reached USD 327 billion in 2024, with 57% uninsured. Between 1980–2024, Nat Cats caused an estimated USD 6.9 trillion in property losses, of which two thirds were uninsured. These uninsured losses act as a drag on economic recovery and push governments into slow, unpredictable, and budget-destabilising post-disaster relief.

Sharing losses is only part of the answer. Investing in risk reduction – measures that prevent or mitigate losses and support recovery and adaptation – is often more cost-effective than rebuilding. Insurance can complement these efforts by spreading remaining losses and providing rapid, pre-arranged liquidity that keeps firms open, preserves jobs, and reduces the need for ex-post fiscal support.

However, private-market mechanisms often do not, on their own, generate sufficient risk reduction or insurance coverage. Individuals underinvest in protection and insurance due to limited budgets, behavioural biases, and expectations of government aid. Insurers may be unable or unwilling to cover large, uncertain, and correlated risks at prices customers can afford. This creates a clear economic and fiscal rationale for government intervention to narrow the disaster protection gap to an efficient and socially acceptable level.

A three-pillar strategy

This report proposes a proactive, three-pillar strategy to narrow disaster protection gaps:

PPIPs: Successes and challenges

PPIPs are already a prominent feature of the global insurance landscape. This report analyses fourteen existing PPIPs across natural and man-made perils. Many have delivered on their core mission. France’s Caisse Centrale de Réassurance (CCR), Spain’s Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros (CCS), and New Zealand’s Natural Hazards Commission (NHC) achieve near-universal coverage for key perils. Pool Re (UK) and the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (TRIP, US) restored capacity after major terrorist attacks when private markets withdrew.

Yet, PPIPs involve significant design challenges. This report’s analysis revolves around the four guardrails that a PPIP must navigate, reflecting fiscal, market, social, and operational constraints:

Our analysis shows that many current PPIPs have stretched one or more of these guardrails. Several have experienced severe financial strain, including the US National Flood Insurance Program’s (NFIP) enormous debt burden; capital losses at France’s CCR after recent droughts; and New Zealand’s NHC drawing heavily on private capital and Treasury support after major earthquakes. Market distortions arise when state-backed reinsurance crowds out private capacity, as in France, where CCR covers most catastrophe reinsurance; or when solidarity pricing dulls risk signals and sustains development in high-risk areas, as in the cases of Flood Re (UK) and the NFIP in the US. Broad risk pools can favour higher-income households in exposed areas, exacerbating economic inequalities, while attempts to reintroduce risk-based pricing in the NFIP have triggered political backlash. Operationally, some schemes pay quickly, but others face disputes over claims, processing delays, and some exhibit high loss ratios, as seen in Australia’s recent Cyclone Reinsurance Pool.

From sharing risks to supporting risk reduction

In many countries, Pillar 3 interventions have preceded strong Pillar 1 initiatives, making coverage available and affordable before, and often instead of, effective risk reduction strategies. This approach is reaching its limits: while PPIPs can slow the widening of protection gaps, they cannot narrow them if risk itself continues to increase.

This report calls for policymakers to treat PPIPs as part of a broader resilience strategy, not as standalone financial tools. PPIPs must not only share disaster losses but also support – or at least not undermine – public and private initiatives to reduce risk. Their legitimacy will increasingly depend on how their Pillar 3 functions reinforce Pillar 1 objectives.

Decision-process and design principles

Because PPIPs are costly and complex, the report proposes a four-step process to assess the need for and potential role of a PPIP:

Based on the comparative analysis, the report outlines key principles for designing or reforming PPIPs to remain within fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails and contribute to resilience. These principles relate to:

Emerging risks: Cyber and pandemic-related business interruption

Applying this framework to two emerging risks in which new PPIPs are being actively considered suggests some important lessons:

Conclusion

PPIPs are often essential tools for maintaining insurability of disaster risks. To ensure viability in a world of rising, increasingly systemic risks, their design and operations need to be part of a proactive risk management strategy that prioritises risk reduction, preserves market discipline, protects public finances, and maintains social legitimacy.

Economic losses from disasters are increasing, leaving a large and widening protection gap that represents the uninsured share of economic losses. This section shows how protection gaps and the costs of post-disaster relief strain public finances and slow economic recovery. It argues for a proactive strategy that prioritises risk reduction and implements efficient risk-sharing mechanisms for residual losses. The rest of the report focuses on public-private insurance programmes (PPIPs) as a key, but complex, component of this strategy.

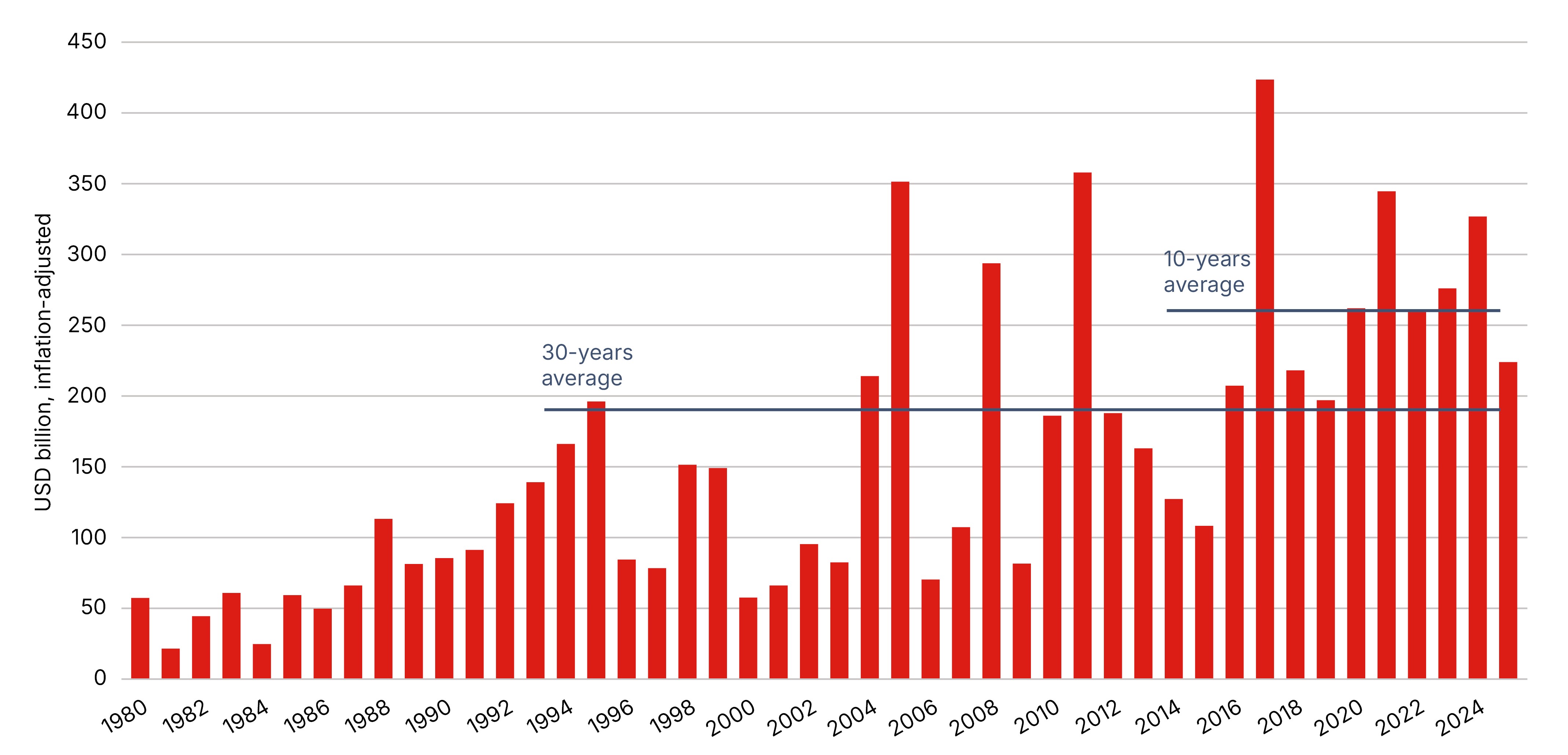

The United Nations defines disaster as “serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses which exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources.” Economic losses from disasters have increased over recent decades (see Figure 1), mainly attributable to rising natural catastrophe (Nat Cat) losses. Nat Cat losses totalled USD 277 in 2023, USD 327 billion in 2024, and around USD 224 billion in 2025, with a 10-year average of USD 262 billion and a 30-year average of USD 190 billion (inflation-adjusted).1

FIGURE 1: TOTAL ECONOMIC LOSSES FROM NATURAL DISASTERS (EXCLUDING DROUGHT AND HEATWAVE) IN USD AS OF 2025, INFLATION-ADJUSTED TO 2025, BETWEEN 1980 AND 2024

Source: Munich Re, NatCatSERVICE, May 20252, and Munich Re3

Record-breaking events are the new norm. Natural disasters, terrorist attacks, or pandemics can hit economies as hard as wars or financial crises.4 Although difficult to measure, the disaster protection gaps are significant. For example, Nat Cats caused an estimated USD 6.9 trillion in property losses from 1980 to 2024 (inflation-adjusted), 67% of which were uninsured.5 Disaster protection gaps will likely continue to widen across all perils, including cyber, through 2030.6

The consequences of disasters reach well beyond direct asset damage.7 The IMF estimates that, on average, disasters cut annual gross domestic product (GDP) by 1.3% in affected countries.8,9 These losses reflect not only destroyed assets but also indirect impacts, such as supply-chain disruption.10 Although reconstruction may briefly lift GDP, national or regional economies with low financial buffers often suffer lasting losses.11,12 They struggle to absorb immediate income shocks and to rebuild quickly, often due to credit and fiscal constraints, institutional weaknesses, or production linkages that transmit shocks across sectors.

When disaster losses are uninsured or underinsured, governments often step in to provide relief to households and firms. Such aid, however, is typically slow, insufficient, and unpredictable.13 It can also destabilise public finances if it strains budgets and debt service obligations.

Ex-ante risk-sharing mechanisms, such as insurance, can offer a more efficient alternative by spreading potential losses across many actors so that no single participant bears the full cost of an event. By providing rapid, pre-committed liquidity to disaster victims, insurance eases cash flow and borrowing constraints. This allows businesses to stay open, preserving employment, enabling output to rebound sooner, and reducing the need for taxpayer-funded aid.14 As a result, research suggests insured disasters are more likely to have temporary rather than permanent macroeconomic effects, a hallmark of resilience.15,16

However, sharing losses is only part of the solution. Investing in risk reduction measures (through actions that prevent or mitigate losses and foster recovery and adaptation) can save up to USD 4–15 in future losses for every dollar spent.17 A proactive strategy that combines risk reduction measures with the risk-sharing mechanisms of insurance can provide significant macroeconomic benefits.

While individuals and businesses would undoubtedly prefer to avoid or minimise losses, private markets alone, such as property or insurance markets, may be unable to both reduce risks sufficiently or share risks at scale. This creates the economic and fiscal case for government intervention to narrow the disaster protection gap to an economically efficient and societally desirable level.18

PPIPs share risks and costs across public and private stakeholders – households, firms, re/insurers, governments, and potentially capital markets – to make insurance more available, more affordable, and to boost uptake in a way that neither public nor private sector could on its own. Such partnerships are not new; many countries have long-standing schemes, such as New Zealand’s 80-year-old earthquake programme. Historically, these schemes were founded reactively, often in the aftermath of a major disaster. However, persistent protection gaps are now prompting many jurisdictions to explore PPIPs proactively, rather than waiting for a crisis to force action:

A shift to proactive risk management requires more than financial or technical tools; it requires a social contract in which societies explicitly decide who invests in risk reduction and how losses are shared among households, businesses, re/insurers, and the state.21,22 This report explores the role PPIPs play in such a social contract. Insurability becomes a political choice, not just a technical issue, shaped by public investment in resilience, market-enhancing policies, and public-private risk-sharing mechanisms.23

Establishing PPIPs involves complex trade-offs with significant implications for public finances, markets, and social equity. This report, therefore, seeks to understand when such partnerships are viewed as necessary and how they operate.

Finally, Section 7 synthesises these findings into concrete recommendations for designing sustainable PPIPs that are fit for an era of growing and emerging risks.

Section 1 shows why disaster protection gaps may require state intervention. An effective strategy must address the root causes of these gaps. Understanding these causes is therefore crucial for developing adequate policy responses to reduce risk and increase risk coverage. This section describes the underlying causes of disaster protection gaps and outlines a three-pillar proactive approach to tackle them.

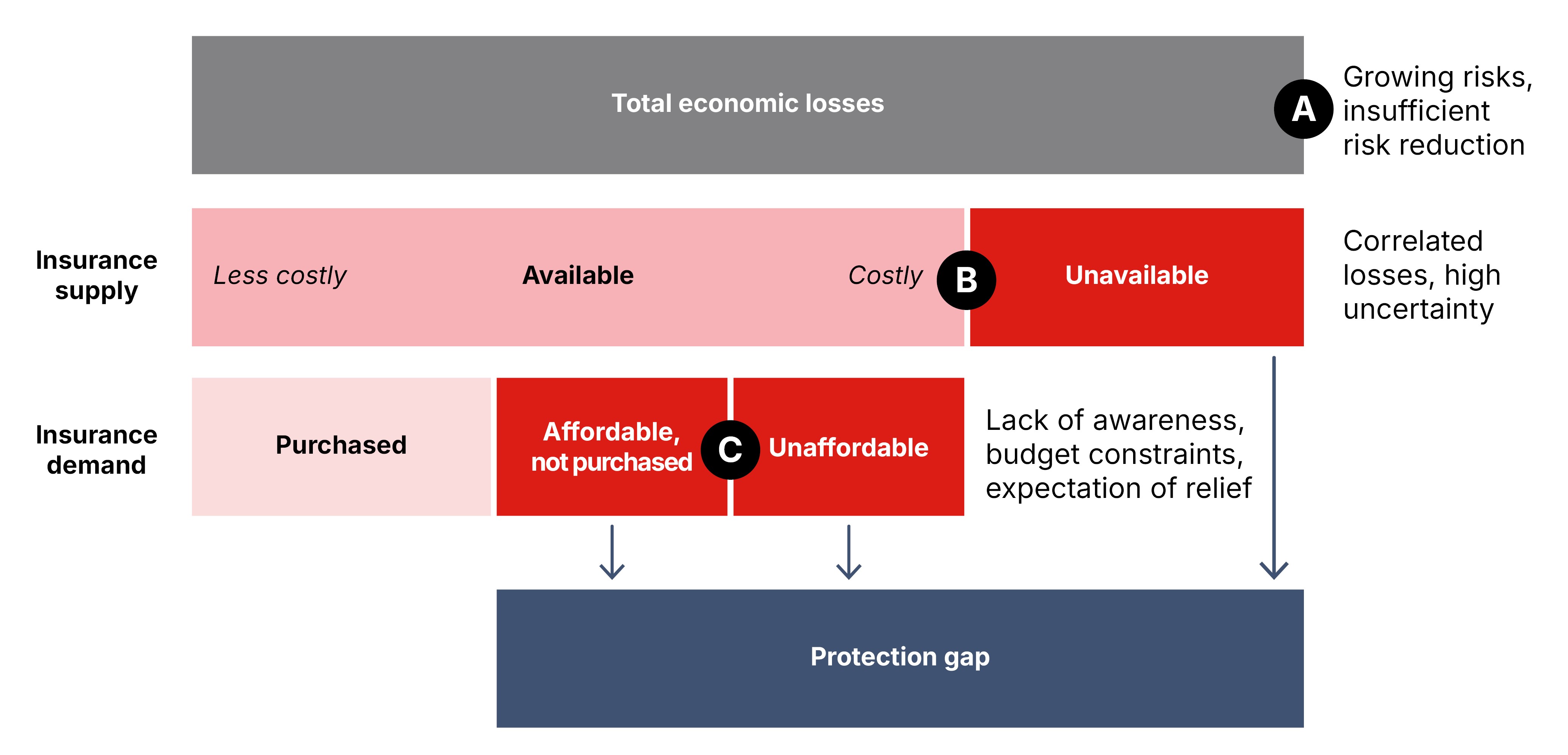

Persistent protection gaps reflect structural frictions in both insurance markets and public policy. This report identifies three root causes (see Figure 2):

A. On the economic-loss side, risk reduction strategies may not keep pace with rising hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities.

B. On the insurance-supply side, the potential for significant losses and their uncertainty – defined as the difficulty of quantifying the likelihood and severity of losses – may lead to coverage being either unavailable or available but unaffordable.

C. On the insurance-demand side, households and businesses may fail to purchase sufficient insurance due to unaffordability, insufficient risk awareness, or expectations of government relief.

FIGURE 2: CAUSES OF PROTECTION GAPS: A. GROWING RISKS AND UNDERINVESTMENT IN RISK REDUCTION; B. COSTLY OR UNAVAILABLE COVERAGE; C. INSUFFICIENT COVERAGE DEMAND. BLOCK SIZES ARE FOR ILLUSTRATION PURPOSES.

Source: Geneva Association

2.1.1 Growing risks and insufficient risk reduction

Risk is rising as its three components increase: hazard (event frequency/severity), exposure (people/assets in danger), and vulnerability (ease of damage).24 New hazards are emerging (e.g. cyberattacks and chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear – or CBRN – terrorism), while existing risks, such as climate extremes, are intensifying.25 Exposures are growing as urbanisation concentrates assets in potentially high-risk areas, economies increasingly depend on intangible assets such as supply chains, and digitalisation expands cyberattack surfaces. Vulnerability is also increasing in some areas due to weak land-use planning, building codes, and cybersecurity. As a result, many households and firms face new and worsening risks, including weather-related events, cyberattacks, and pandemics. Many of these risks have systemic potential: a single disruption in energy, transport, or digital infrastructure can cascade across sectors and regions through disrupted supply chains, amplifying losses. At the same time, uncertainty is growing due to limited historical data about new or changing risks. Consequently, some risks grow or evolve faster than societies can respond to them.26

Risk reduction occurs at the individual level (e.g. home retrofits) to protect single properties and at the community level (e.g. flood barriers or land-use rules) to protect entire areas. Even though risks are rising, both forms of risk reduction remain underfunded:

In addition, individuals and public entities alike often lack robust risk-reduction cost-benefit data, hindering the effective prioritisation and financing of interventions.28

2.1.2 Costly or unavailable re/insurance coverage

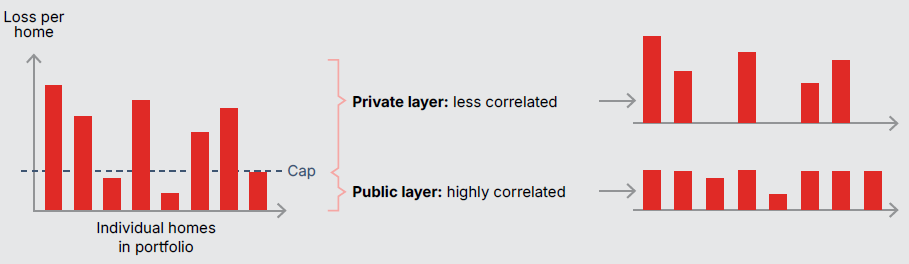

Business lines, such as motor insurance, rely on diversification: pooling many independent risks reduces the volatility of the average claim, as the law of large numbers predicts. Pooling thus lowers required capital per policy, bringing diversification benefits. This actuarial logic breaks down for disasters, as dependencies lead to simultaneous losses across individual and business lines, undermining diversification. Average claims’ volatility subsequently remains high or might increase with pooling, leading to a surge in re/insurers’ capital needs, thus inflating premiums.29 On top of this, uncertainty increases the capital costs re/insurers must pay to compensate investors for absorbing unpredictable future losses.

Simultaneous losses and heightened uncertainty have two consequences:

Reinsurers provide additional capacity by spreading exposures globally, absorbing insurers’ tail risk. Capital markets, through insurance-linked securities (ILS), can further increase available capital by tapping into diversified investor portfolios. However, even these mechanisms hit structural limits to diversification.32

2.1.3 Low disaster insurance uptake

Even when disaster insurance is available, uptake may be low. The reasons are frequently similar to the ones that lead to under-investment in risk reduction. These factors include:

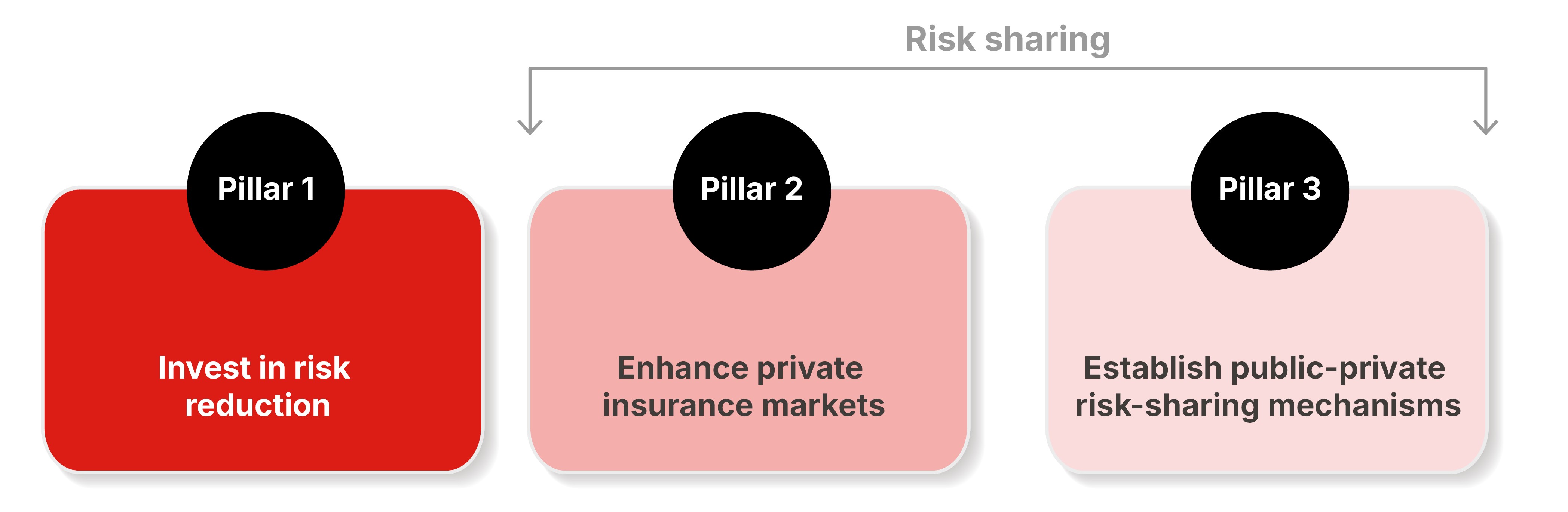

A proactive risk-management strategy must address the causes of the protection gap. This strategy rests on three pillars: one based on risk reduction; and the other two on risk-sharing (see Figure 3).37

Figure 3: A proactive three-pillar strategy for governments to reduce and share risks

Source: Geneva Association, adapted from Zurich Insurance Group

These three pillars, ordered from least to most market-distorting, represent an ideal order of priority. Risk reduction (Pillar 1) takes precedence whenever it is the most cost-effective option. Ideally, societies would invest in prevention and adaptation until the additional costs of further risk reduction outweigh the benefits. Only then should any remaining residual risk be transferred via private markets and, potentially, PPIPs.

This framework relies on a clear understanding of shared responsibilities, with the government orchestrating a national risk-management strategy:

Section 2 introduces the rationale for PPIPs (Pillar 3) as state interventions that alter market operations to improve risk-sharing. Economic theory and practice show that attempts to correct a particular market distortion can introduce new distortions, potentially reducing rather than improving overall market efficiency.38 Moreover, PPIPs have significant impacts beyond re/insurance markets: they typically expose the state to fiscal risk and may involve redistributive mechanisms with implications for social equity. The successful design of a PPIP therefore requires a conceptual framework that captures these implications.

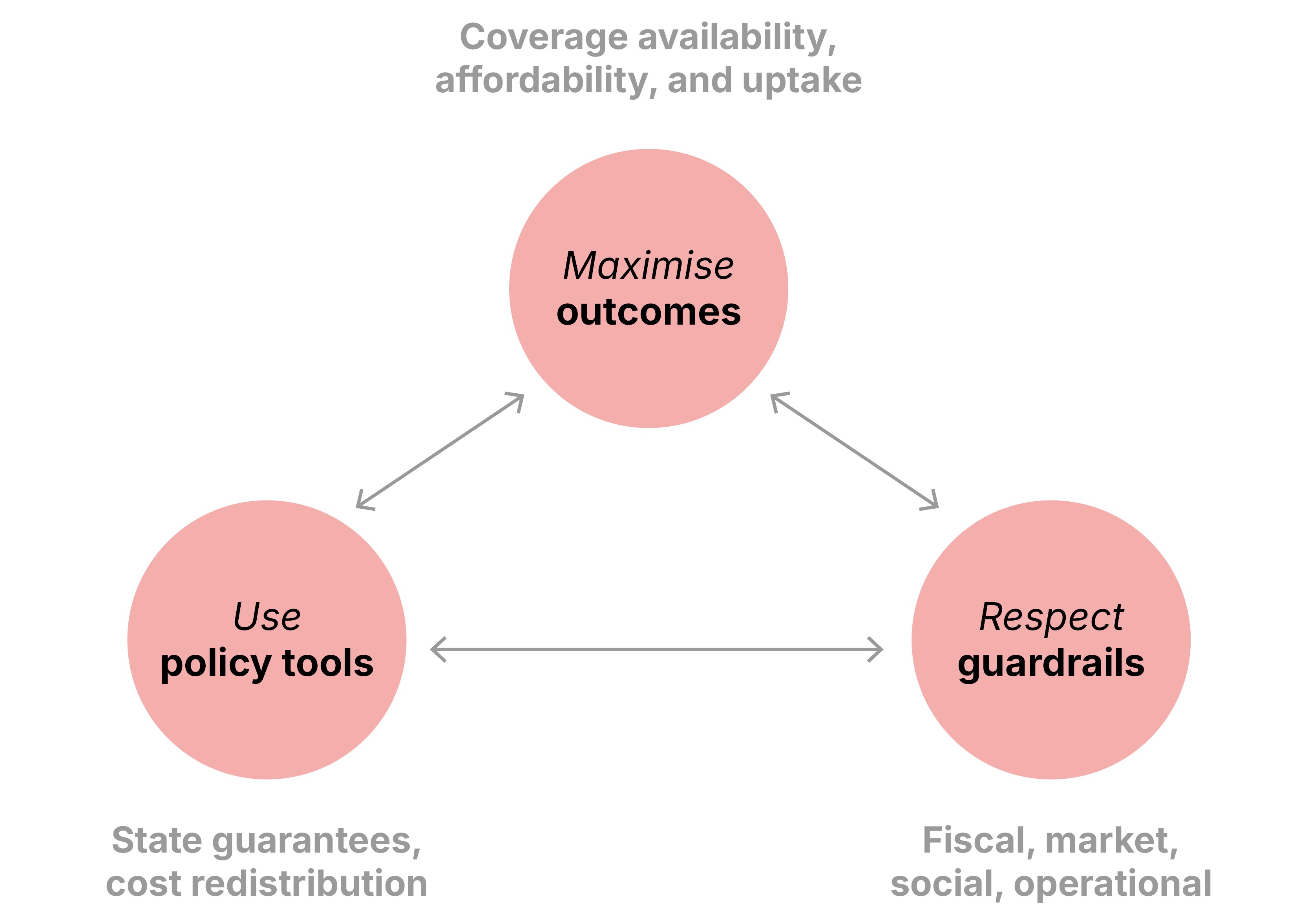

Designing a PPIP is a complex policy optimisation problem that seeks to maximise societal well-being and market efficiency. This problem has three core components (see Figure 4):

Figure 4: Designing a PPIP is an optimisation problem

Source: Geneva Association

Policymakers face a challenge: deploying each policy tool to achieve coverage outcomes may collide with or even overstep guardrails. This requires policymakers to evaluate trade-offs:

Each PPIP must secure its social license – broad societal acceptance – by delivering expected outcomes and navigating guardrails in line with societal norms. How PPIPs seek to achieve their objectives while remaining within their guardrails reflects societal expectations and preferences, which explains why schemes differ across countries and perils.

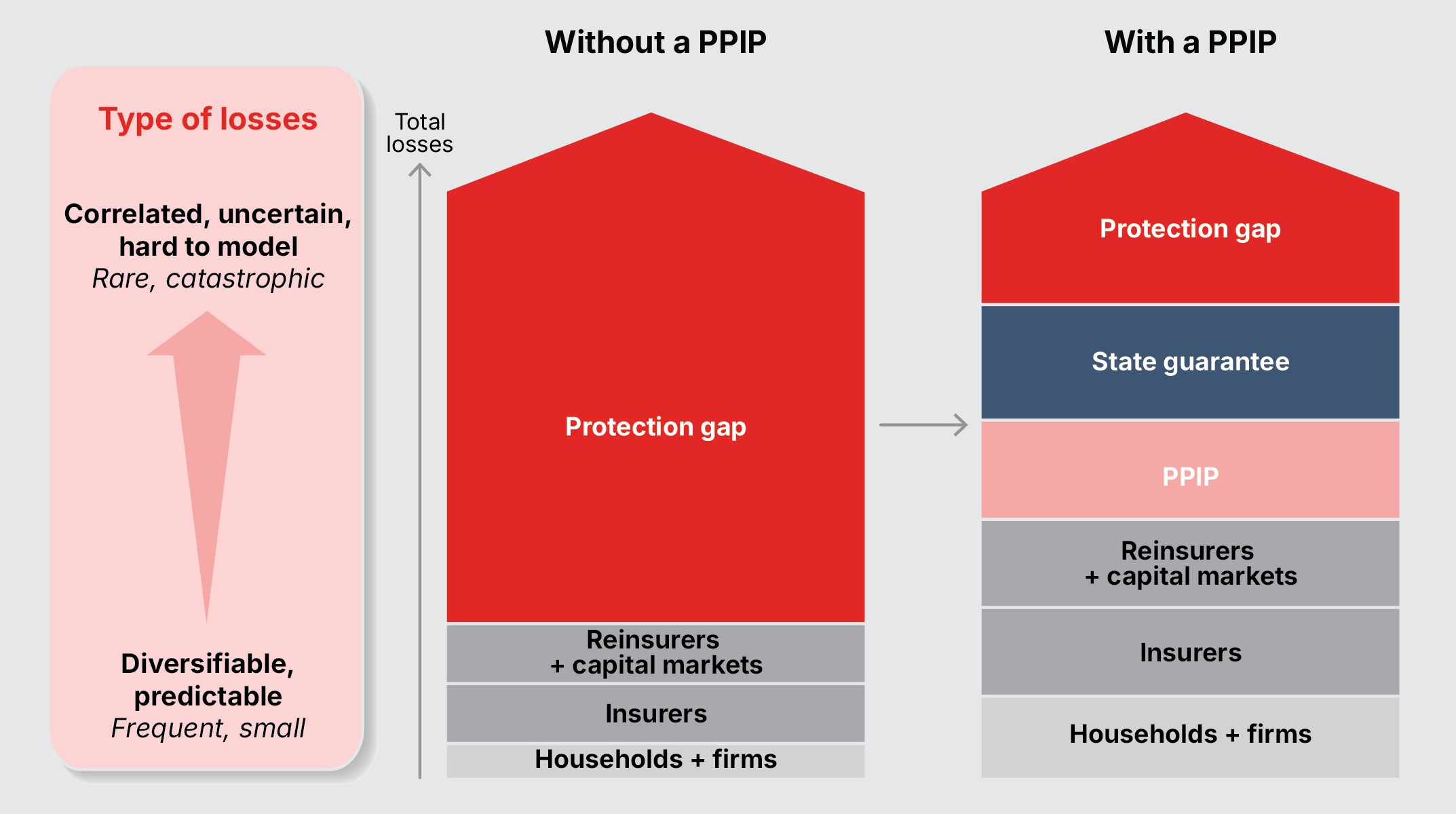

Box 1: How state guarantees make disasters more insurable

Efficient risk-sharing relies on loss layering, allocating risk based on frequency and severity (see Figure 5, left):44

Therefore, state guarantees make disasters more insurable by catalysing capital accumulation.47 As private and PPIP capacity grow, the state guarantee can move up to cover increasingly less frequent losses, lowering fiscal risk.

FIGURE 5: How state guarantees make risks more insurable by catalysing capital accumulation

Source: Geneva Association

Drawing on findings from the analysis of fourteen PPIPs across five peril classes (see Table 1), this section explores the specific design choices used to implement state guarantees and cost redistribution while respecting agreed guardrails. Readers interested in the specific features of individual schemes can refer to the detailed table in the appendix.48

TABLE 1: THE PPIPs ANALYSED IN THIS REPORT

Name | Peril 49 | Country |

| Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation, Terrorism Pool (ARPC-Cyclone) | Terrorism | Australia |

| Gestion de l’Assurance et de la Réassurance des Risques Attentats et Actes de Terrorisme (GAREAT) | France | |

| Extremus | Germany | |

| Pool Re | UK | |

| Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (TRIP) | US | |

| Japan Earthquake Reinsurance Company (JER) | Earthquakes | Japan |

| Natural Hazards Commission – Toka Tū Ake (NHC) | New Zealand | |

| Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool (TCIP) | Türkyie | |

| California Earthquake Authority (CEA) | US | |

| Caisse Centrale de Réassurance (CCR) | Nat Cats | France |

| Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros (CCS) | Spain | |

| Flood Re | Floods | UK |

| National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) | US | |

| Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation, Terrorism Pool (ARPC-Cyclone) | Cyclones | Australia |

Source: Geneva Association

The sample covers a range of natural and man-made hazards, mostly in developed countries. While they serve comparable policy objectives, these PPIPs differ widely in how they navigate trade-offs between fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails. This shows that there is no unique blueprint: each design reflects the conditions – societal, economic, political, or regional – under which the PPIP formed. Moreover, some PPIPs in our sample have operated for decades (e.g. France’s CCR) and others for a few years (e.g. Australia’s ARPC-Cyclone), shedding light on long-term challenges and illustrating recent trends.

The sample covers a range of natural and man-made hazards, mostly in developed countries. While they serve comparable policy objectives, these PPIPs differ widely in how they navigate trade-offs between fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails. This shows that there is no unique blueprint: each design reflects the conditions – societal, economic, political, or regional – under which the PPIP formed. Moreover, some PPIPs in our sample have operated for decades (e.g. France’s CCR) and others for a few years (e.g. Australia’s ARPC-Cyclone), shedding light on long-term challenges and illustrating recent trends.

A. Scope of coverage: What does the guarantee cover?

A PPIP’s scope defines the specific protection gap that the state guarantee addresses.

Key choices:

Trade-offs:

A narrow scope keeps premiums affordable and limits the chance of hitting fiscal constraints. In fact, a well-calibrated cap can absorb most losses, stabilising livelihoods after a disaster. 51 Moreover, it can stimulate private markets into providing top-up coverage, aligning with the market guardrail. Conversely, a broad scope better reduces protection gaps and brings diversification benefits and economies of scale.52 However, this may expose the state to larger losses and crowd out private capacity, testing the fiscal and market guardrails.

Box 2: How New Zealand’s NHC balances public and private shares of risk

Designing PPIPs is a balancing act: the state should absorb some risk, but not too much. New Zealand’s NHC provides a real-world example of this optimisation.

The NHC state-backed cover acts as a public deductible (currently NZD 300,000 per property). This cap is designed to solve an insurability problem for private markets, as illustrated in Figure 6. Losses below the cap represent the small-to-medium first loss damages from an earthquake. The key issue for insurers is that these losses can occur simultaneously across all exposed properties. As discussed in Section 2.1.3, highly correlated losses cannot be diversified away, driving up capital costs. Losses above the cap, however, correspond to rarer types of damage. These top-up losses are also more independent from home to home.

By absorbing correlated first losses, the NHC leaves private insurers not only with lower expected losses to cover, but also with a risk that is more diversifiable and thus more insurable.53 This enables the private market to offer top-up policies at risk-based yet affordable prices. NHC regularly adjusts the cap as construction costs climb, aiming to “keep private top-up cover affordable and attractive.”54 Each cap increase further challenges the fiscal guardrail but supports affordability and private coverage uptake, illustrating the trade-offs PPIPs face.

FIGURE 6 HOW THE NHC’S CAP ABSORBS THE MOST CORRELATED PART OF DISASTER LOSSES

Source: Geneva Association

B. Market role: Insurer, reinsurer, or backstop?

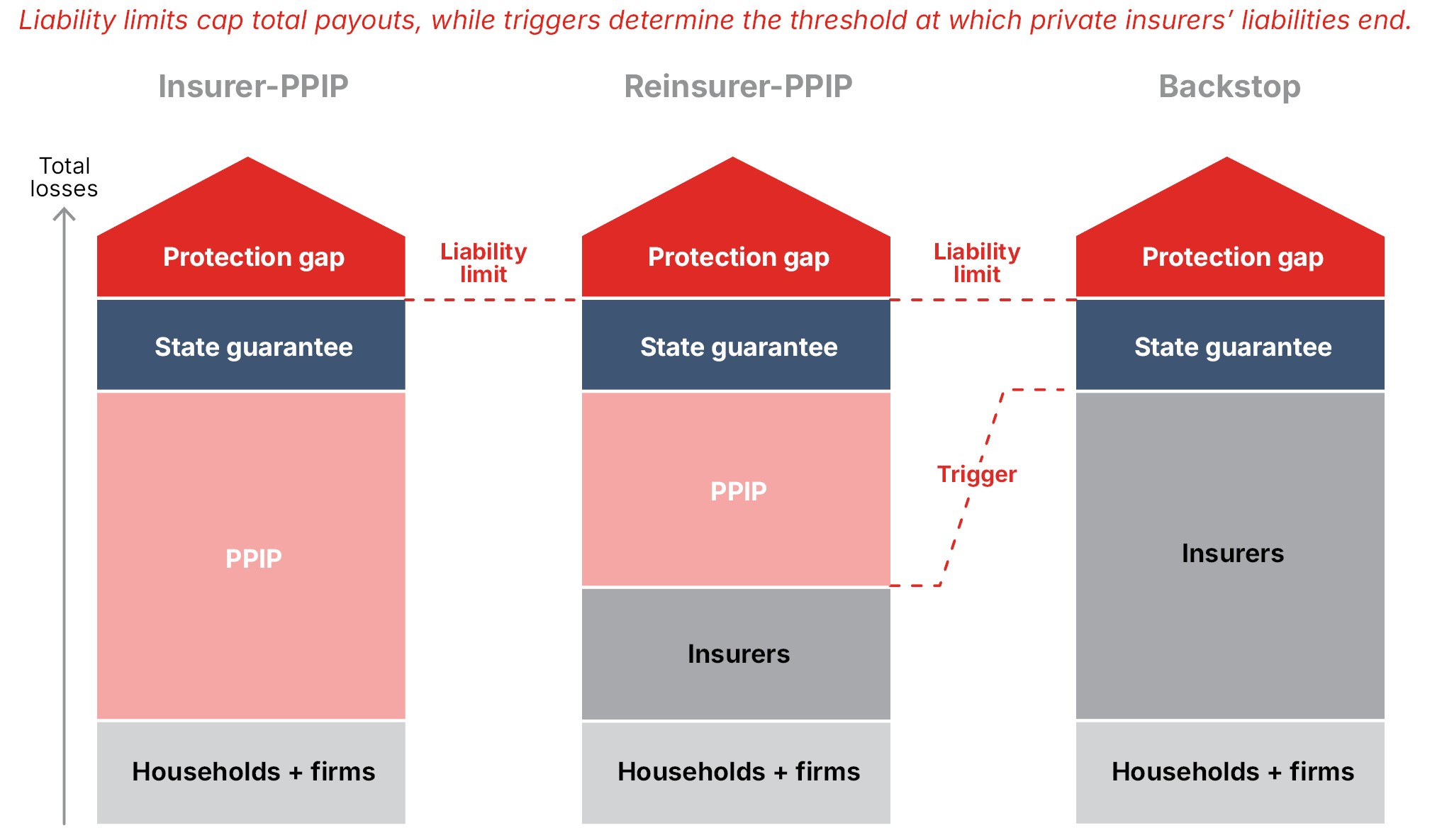

The most visible aspect of state guarantees is how they interface with the insurance market (see Figure 7).

Key choices:

Trade-offs:

Insurer-PPIPs arise when insurance penetration is very low, or coverage is unavailable, as the government assumes direct financial risk – essentially replacing the private market for eligible perils and exposures. Reinsurer-PPIPs or backstops typically arise when private capital is unavailable for disaster-level losses (e.g. Pool Re in the UK or TRIP in the US) or when regulation mandates that insurers offer disaster coverage (e.g. Japan’s JER, France’s CCR). Insurer-PPIPs are more likely to strain fiscal guardrails, as they assume all eligible losses. Conversely, reinsurer-PPIPs help maintain market discipline at the direct insurance level.

C. Payout structure: Triggers and liability limits

The mechanics of the state guarantee clarify how much capital is available when disaster strikes and what share the private sector provides.

Key choices:

Figure 7 illustrates how liability limits cap total payouts, while triggers mark the transition from private insurer liabilities (including those ceded to private reinsurers) to reinsurer-PPIP or backstop liabilities. For reinsurer-PPIPs, the trigger corresponds to the sum of insurers’ retentions. In TRIP (US), a backstop, the trigger defines the losses insurers must bear before fiscal support kicks in.58

Trade-offs:

If the trigger is set too low, the reinsurer-PPIP or backstop crowds out private insurers by covering insurable losses, straining the market guardrail; if set too high, a protection gap remains. Calibrating liability limits and triggers, thus, ideally relies on robust risk data and modelling. However, where uncertainty is high, calibration focuses on determining the maximum level of risk the private market’s capital base can sustainably retain, ensuring the state acts strictly as a reinsurer of last resort.

The state’s fiscal commitment varies, reflecting different approaches to managing the fiscal guardrail. In Japan, the state guarantee accounts for 97.2% of JER’s JPY 12 trillion liability limit, while in the US, the state bears around 33% of TRIP’s USD 100 billion liability limit. Some schemes benefit from unlimited state guarantees and, therefore, have no liability limits. They cover all eligible losses above the trigger, further narrowing protection gaps but creating open-ended fiscal liabilities that push the fiscal guardrail.

FIGURE 7: LOSS ALLOCATION ACROSS THREE TIERS: 1) INSURERS, 2) PPIP (OWN CAPACITY), AND 3) STATE GUARANTEE Liability limits cap

Source: Geneva Association

Finally, two PPIPs rely on industry levies instead of state guarantees. These are mandatory post-event contributions collected from insurers or policyholders. This removes fiscal exposure, shifting the cost of disasters onto insurers and policyholders. For example, should available funds run out, Flood Re can impose an unlimited Levy 2 on all UK home insurers. Similarly, California’s CEA can levy USD 1 billion from policyholders and USD 1.6 billion from participating insurers. While protecting public finances, post-disaster levies can lead to premium increases or delays in claims payments, potentially straining social and operational guardrails.

D. Capital strategy: Buffering the state guarantee

Capital strategies determine how PPIPs manage the risk on their own balance sheet (in Figure 7, PPIP layers).

Key choices:

Trade-offs:

Own capital accumulation works best for low-frequency perils such as earthquakes or terrorism, with long return periods. In the face of such perils, capital accumulation is essential for managing the fiscal guardrail, creating a buffer – as in the UK’s Pool Re, with GBP 7 billion in accumulated funds – that ensures the state guarantee is triggered only rarely. A capital mix that includes reinsurance and ILS, however, helps maintain the market guardrail by shifting more risk to private markets and connecting PPIPs to private pricing and risk signals. This also provides PPIPs with renewable capital and leverages global diversification, but exposes them to pricing volatility, potentially straining the operational guardrail.

E. The cost of the state guarantee

Unlike post-disaster aid, which often is a non-repayable transfer, governments can charge for state guarantees.

Key choices:

Trade-offs:

Upfront fees, which act as a premium to compensate the state for its risk-bearing capacity, monetise the state’s commitment. For example, Pool Re (UK) has transferred over GBP 2 billion to the Treasury since its inception, in return for a state guarantee that has never been triggered. Upfront fees help maintain financial discipline in a PPIP by reflecting the cost of fiscal risk. They also provide predictability. This also raises the technical challenge of setting a price for risks that are difficult to quantify. Post-event recoupment, on the other hand, avoids immediate costs for the PPIP but may further strain its finances after major disasters and lead to premium increases, potentially straining the social and operational guardrails.

While state guarantees lower premiums, some PPIPs rely on cost redistribution to further boost coverage affordability and uptake.

A. Compulsion

To overcome low uptake, selling or purchasing insurance coverage may be required by law or regulation.

Key choices:

Compulsion also exists in reinsurer-PPIPs. ARPC (Australia) and GAREAT (France) require all insurers to cede all eligible policies to the PPIP. While cession is voluntary, insurers who choose to cede policies to Pool Re (UK) or ARPC-Terrorism (Australia) must cede all their eligible policies. Such mandates lessen adverse selection.

Trade-offs:

Demand-side mandates or compulsory bundling, which impose costs on consumers, are politically sensitive. Thus, PPIPs often combine them with solidarity pricing (New Zealand’s NHC, France’s CCR) or a low coverage cap (Türkiye’s TCIP) to keep prices down. Conversely, compulsion may be necessary to implement solidarity pricing, ensuring a diversified pool and avoiding adverse selection.

Compared to voluntary systems, compulsion ensures higher uptake, larger and more stable re/insurance pools, and thus lower prices, potentially aligning with social guardrails. However, compulsion restricts choice, weakens underwriting practices, and raises fiscal commitments, weakening both market and fiscal guardrails. It also requires enforcement to be effective, an operational constraint.

B. Pricing approach

In our sample, a PPIP’s pricing of disaster risk ranges from risk based (premiums match actual risk levels) to solidarity based (lowering premiums for high-risk groups).62

Key choices:

Trade-offs:

Risk-based pricing creates economic signals that direct investment toward risk reduction, which respects the market guardrail. However, it is data-intensive and can entrench unaffordability in high-risk areas, potentially straining the social guardrail. Conversely, solidarity pricing improves affordability and uptake but weakens risk-reduction incentives and market discipline. It may also raise fairness concerns when subsidies do not benefit the most vulnerable.

This section discusses the drivers behind the creation of featured PPIPs; before assessing their real-world performance and how they navigate fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails. Most PPIPs have succeeded in improving insurance availability, affordability, and uptake. Yet many struggle to stay within one or more guardrails. Some schemes have stifled private insurance markets while others have exposed the state to rising fiscal risk. Moreover, new or growing risks drive up loss volatility, testing the limits of even well-designed PPIPs, highlighting the need for greater risk reduction (Pillar 1), an issue explored in the next section.

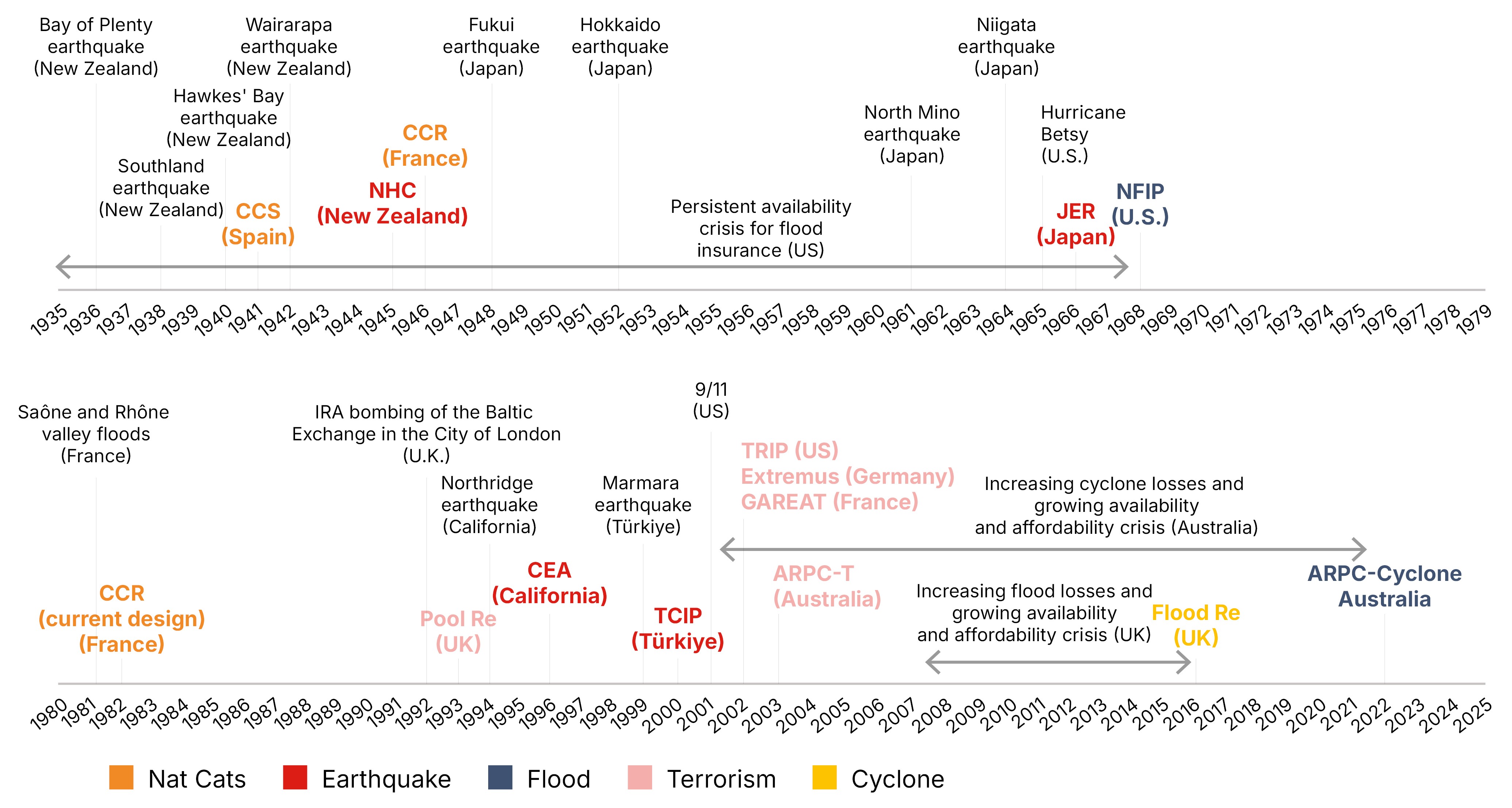

The history of existing PPIPs shows that a crisis often triggers their creation (see Box 3 and Figure 8):

Box 3: When a disaster triggers action

Four of the five terrorism-related schemes analysed – TRIP (US), GAREAT (France), Extremus (Germany), and ARPC-Terrorism (Australia) – emerged in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. The UK’s Pool Re was established in 1993 after the IRA bombing of London’s Baltic Exchange. These PPIPs addressed severe reinsurance shortfalls when terrorism risk, previously underestimated, became largely uninsurable, affecting critical sectors such as aviation, tourism, and commercial real estate lending.

Similarly, the four earthquake PPIPs were triggered by major earthquakes, often after private insurers had already withdrawn from the market (Japan, New Zealand) or where insurance penetration was minimal (Türkyie), following decades of costly losses. In California, home insurers are mandated to offer earthquake insurance alongside basic coverage, meaning that insurers cannot selectively withdraw capacity for earthquake risk. The CEA aimed to stabilise the homeowners’ market after insurer withdrawals following the 1994 Northridge quake, due to previously underestimated losses.

Finally, France’s CCR was implemented in 1982 after a series of severe floods between late 1981 and early 1982 revealed a significant protection gap, insurance being either too costly or unavailable.

Source: Geneva Association

Figure 8: Timeline creation of PPIPs

Source: Geneva Association

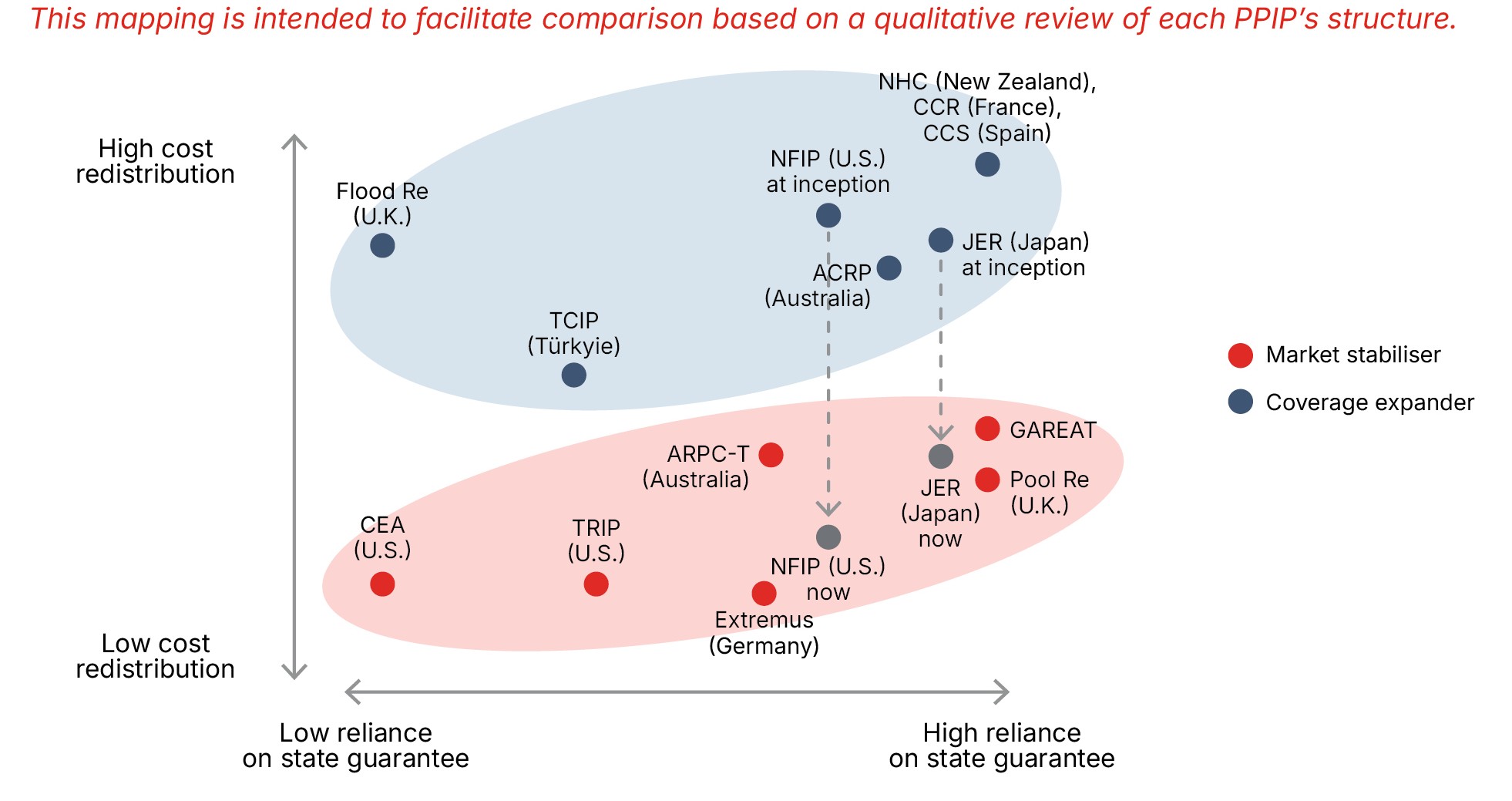

When examining the performance of existing PPIPs, two archetypes emerge, reflecting different objectives and choices made regarding the policy trade-offs discussed earlier. Understanding these archetypes helps frame the assessment of their successes and challenges (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Two PPIP archetypes

Source: Geneva Association

In our sample, all terrorism PPIPs, as well as California’s CEA (earthquakes), are market stabilisers (Figure 10).

Figure 10: State guarantees vs. cost redistribution and PPIP archetypes

Source: Geneva Association

PPIPs with a market-stabiliser archetype have restored availability and price stability in markets experiencing reinsurance shortfalls or pricing spikes. Reviews of TRIP (US), ARPC-Terrorism (Australia), and Pool Re (UK) consistently highlight their role in preventing market failure.65 However, because most market stabilisers rely on voluntary coverage and risk-based pricing, protection gaps remain where coverage is expensive or potential customers lack awareness. For example, only 4% of UK SMEs carry terrorism cover.66 CEA (California) reaches fewer than 15% of homeowners.

Coverage expanders that combine compulsion and solidarity pricing achieve the highest coverage and improve affordability the most. NHC (New Zealand, CCR (France), and CCS (Spain), which use compulsory bundling and solidarity pricing, achieve uptake of around 90–95%.67 ARPC-Cyclone reduced cyclone premiums in high-risk areas by around one-third and raised quote success rates from 66% to 84% in its first year. Before Flood Re (UK), only 8% of high-risk households could obtain more than two quotes; now 99% can get fifteen or more.68

Conversely, coverage expanders that rely on voluntary participation struggle to increase insurance uptake. In the US, NFIP take-up is around 30% in flood zones. In California, 89% of policyholders opt out of the CEA’s earthquake coverage. In Japan, only 35% of households have fire insurance, although the earthquake add-on rate rose from 33% in 2001 to 70% in 2023, indicating increased risk awareness. Despite a purchase mandate, Türkiye’s TCIP’s weak enforcement leaves 40% of eligible households uninsured.

For both market-stabiliser and coverage-expander archetypes, moreover, protection gaps persist for perils and exposures outside scheme mandates. These include CBRN or cyber risks for some terrorism PPIPs, commercial property in earthquake schemes, or post-2009 homes and dwellings of over three units in Flood Re (UK). Likewise, because ARPC-Cyclone (Australia) only covers cyclone-related losses, property insurance prices keep rising or remain unaffordable in regions exposed to other types of flooding.69

Finally, these PPIPs were established to cover physical property damage and, in some cases, resulting business interruptions.70 Yet, corporate value has shifted to intangible assets and global supply chains.71 While property damage remains an important issue, new exposures, such as data loss and contingent business interruption, which are not tied to physical property damage, may require dedicated solutions.

This subsection examines how PPIPs have navigated the four guardrails outlined in Section 3. Examining their performance through the lens of the guardrails reveals both successes and areas of strain. This often suggests a need for reform, a discussion that is ongoing for several PPIPs.

Fiscal guardrail: Preserving fiscal space

Well-designed PPIPs protect public finances by building capacity for routine losses and making the state a reinsurer of last resort. Across PPIPs, four patterns stand out:

Market guardrail: Not crowding out private markets, ensuring insurers bear a sustainable level of risk, fostering market discipline and innovation

Successful PPIPs crowd in private capital without hollowing out market discipline. Four lessons emerge:

Social guardrail: Ensuring vulnerable groups can access coverage at a price they can afford and that costs and benefits are distributed in a way that is considered fair

PPIPs, especially those with a coverage-expander archetype, derive much of their social license from how they address affordability. Successful schemes manage to broaden participation and protect vulnerable groups.

Operational guardrail: Delivering fast claims-paying ability and adaptability while remaining relevant

Effective PPIPs gain credibility through efficient operations, predictability, and adaptability:

Box 4: Case study: France's CCR – The erosion of guardrails under rising climate risk

France’s CCR exemplifies the complex balancing act facing PPIPs. The choices it makes in prioritising certain guardrails may stretch others, leading to financial strain and contestation.

Solidarity foundation (social guardrail): Created in 1946 to support post-war economic stabilisation, CCR became central to France’s disaster risk management with the 1982 Natural Disaster Insurance Reform. Driven by the French constitutional principle of solidarity in the face of national calamities, this reform made disaster coverage mandatory for property insurance policies. Critically, it mandated flat-rate pricing (a surcharge on property policies regardless of individual risk) and backed insurers with reinsurance from CCR, which benefits from an unlimited state guarantee.

Contestation (market guardrail): While enjoying broad support, the combination of flat pricing and an unlimited state guarantee means CCR offers reinsurance at below-market prices, stifling competition. In 2012, reinsurer SCOR contested the state guarantee before the European Commission, arguing it distorted competition. Although the E.U. General Court upheld CCR’s legality in 2016, the case underscores the tension between the solidarity-based model and market efficiency principles.93

Strain from growing risks (fiscal and operational guardrails): Today, the CCR faces significant strain, primarily due to drought-related clay shrink-swell (retrait-gonflement des argiles or RGA) – a peril ill-suited to the scheme’s original design. RGA involves slow, repeated ground movements, causing costly structural damage. It is gradual, predictable, and non-random, violating key insurability conditions and differing vastly from the acute disasters the 1982 rules envisioned.

Experts agree that current prevention measures cannot stop rising RGA losses, prompting debate over reforms ranging from stronger prevention mandates to removing RGA from the scheme and to entirely socialising disaster insurance.95 This mounting pressure highlights the need to adapt designs to remain within agreed guardrails as risks evolve.

Source: Geneva Association

For many PPIPs, particularly those with a coverage-expander archetype, the strains detailed in Section 5 – from the US NFIP’s chronic debt and the UK’s Flood Re rising costs to capital depletion in France’s CCR or New Zealand’s NHC – highlight how rising risks stretch current designs. This reflects a political reality: PPIPs (Pillar 3) are almost always established before meaningful risk-reduction measures (Pillar 1) are in place.

This section examines how existing PPIPs aim to reduce economic losses from disasters. It points out the limitations of methods that focus solely on changing individual policyholders’ behaviour, before advocating for a fundamental shift in how PPIPs are designed, prioritising measures that also alter risk and behaviour at a collective level.

In an ideal world, risk-sharing measures (Pillars 2 and 3) address the protection gaps that remain after cost-effective risk-reduction measures (Pillar 1) have been exhausted. In practice, however, the urgency of addressing growing availability and affordability pressures, as well as real-world timelines, often means PPIPs (Pillar 3) are implemented before meaningful efforts in Pillar 1 and 2:

When a PPIP relying on solidarity pricing is implemented first, market signals diminish or disappear. Consequently, risk awareness diminishes among policyholders, decreasing incentives to invest in risk mitigation and artificially maintaining property values and population growth in high-risk areas (see Section 5.4).

Moreover, solidarity pricing can trigger public sector moral hazard. By making coverage affordable and available through a PPIP, local authorities can postpone necessary investments or politically difficult adaptation measures, such as relocation. For example, Flood Re (UK) has faced criticism for potentially enabling the deferral of crucial flood defence investments.103 The Association of British Insurers (ABI) has urged for more investment, and Flood Re itself warns that low public investment, climate change, and floodplain development threaten its intended 2039 sunset.104

Similarly, through NFIP, some US states and local governments have benefited from population growth in high-risk areas, for example, through tax revenue, by allowing “two or three times more construction in these risky areas than in safer regions”.105 States receive the benefits of economic development through the NFIP, while the federal government bears the financial costs of flooding. A similar disconnect exists in France, where experts highlight that local authorities tend to support development in high-risk areas, expecting the state-funded CCR to cover the insurance costs.106,107

The US NFIP is the only solidarity-based PPIP in our sample that supported risk reduction from the outset. Today, however, many other PPIPs have incorporated risk-reduction measures into their core design, aiming to align their risk-sharing function (Pillar 3) with risk-reduction objectives (Pillar 1). While some schemes, such as France’s CCR and the US NFIP, support collective prevention measures, most focus on reducing their own loss experience by incentivising policyholders to strengthen their properties. Additionally, or instead, some invest in the sharing of risk models and data, together with education programmes, to support public and private risk-reduction efforts.

A. Integrating with public-policy and community action

PPIPs connect essential stakeholders: policyholders, re/insurers, and various levels of government. Leveraging these connections can facilitate coordinated approaches in which PPIPs support national strategies:

B. Financial incentives for policyholders

More frequently, PPIPs may provide financial incentives for policyholders to invest in risk reduction:

C. Investing in risk knowledge and tools

Through claims data, modelling, and hazard mapping, PPIPs generate information that can guide public policy, such as land-use planning:110

Creating hazard maps and data platforms: The US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which runs NFIP, developed extensive current and future flood maps used for underwriting, community planning, and land zoning.113

Despite these promising initiatives, achieving meaningful risk reduction through PPIPs faces significant hurdles:

Box 5: When risk reduction does not pay off for homeowners

In the US, NFIP provides up to USD 30,000 to elevate or relocate flood-prone homes to bring them into compliance with current regulations. Yet, actual elevation or relocation costs often run three to five times higher than this provision.118,119 Annual discounts for homes with an elevation certificate range from USD 100 to 2,000. A policyholder might spend USD 60,000 to elevate a house, receive a USD 30,000 grant, and save USD 1,000 annually. This implies a 30-year payback period, longer than most ownership spans.120 In such cases, few households invest.

By contrast, in California’s Brace + Bolt programme, subsidies cover actual costs. Brace + Bolt offers homeowners up to USD 3,000 to retrofit pre-1980 homes, with up to USD 10,000 for lower-income homeowners. Retrofitted homes qualify for CEA premium discounts up to 25%. For low-cost projects, grants can cover all expenses; for typical upgrades, they cover 50–75%.121 Combined with premium reductions, this significant subsidy underpins the programme’s uptake, with over 23,000 retrofitted homes across California’s fault lines.

Source: Geneva Association

These challenges show that adding isolated risk-reduction components to existing PPIP is not reliably effective.

In fact, the most significant gains occur when PPIPs are embedded in, and aligned with, national risk-reduction strategies that promote collective, rather than isolated, action:

However, such aligned approaches currently lack scale. France’s RPPs, despite high adoption levels, are expected to be insufficient to prevent rising losses.124 In the US, 56% of CRS communities achieve only the lowest improvement classes (classes 8–9 out of 1–9, with 1 representing the highest standards), which offer limited risk-reduction benefits. The remaining communities reach only mid- to low improvement classes (5–7). CRS communities tend to prioritise easily achievable measures (such as zoning or public information) over more impactful but costlier physical flood-reduction projects.125 In both cases, the system seems to encourage local governments to comply with low or increasingly outdated minimum standards, which effectively serve as regulatory ceilings rather than incentivising more meaningful risk reduction.

In a context of mounting fiscal and operational pressures, policymakers are increasingly aware that some PPIPs can no longer function solely as financial shock absorbers. In many cases, strategies are failing because Pillar 3 (PPIPs) are implemented before Pillar 1 (risk reduction). The new mandate for policymakers is to integrate risk-reduction objectives from the outset or retrofit them into existing schemes. This should ensure that the PPIP’s design actively promotes public and private resilience efforts – or, at least, does not hinder them. The challenge, illustrated in Figure 11, is not just balancing outcomes and guardrails, but ensuring that the PPIP serves as a resilience accelerator: one that actively narrows the gap between individual incentives and necessary collective, government-led action.

Figure 11: PPIPs must not only maximise coverage outcomes (Pillar 3) but also ensure that the PPIP’s design promotes individual

Source: Geneva Association

Even the best-designed PPIP cannot replace a comprehensive national prevention and resilience strategy that combines investments in physical resilience with regulations or incentives for individuals and businesses to manage their own risks. When Pillar 1 is weak, PPIPs might temporarily address availability or affordability issues, but risk worsening long-term fiscal and operational pressures.

The analysis in Sections 5 and 6 highlights both the achievements of PPIPs and the challenges they face. It illustrates successes in stabilising or expanding coverage but also resultant strains on fiscal and market guardrails. It further shows instances where PPIPs undermine risk reduction (Pillar 1). Achieving sustainable PPIPs in a world of rising and changing risks requires a robust national risk-reduction strategy to be in place, with governments leading coordinated efforts across society. Moreover, the design of Pillar 3 (PPIPs) must actively support risk-reduction objectives.

This section outlines ten principles for designing new or reforming existing PPIPs, ensuring they are part of a comprehensive, proactive risk management strategy that prioritises risk reduction whenever feasible. Insights for policymakers considering new PPIPs, including for emerging risks such as systemic cyber and pandemic business interruption losses, are also provided.126

Box 6: A holistic approach to climate risk and resilience

When risks are complex, moving from reactive crisis management to proactive resilience-building requires a comprehensive public investment strategy. Public spending on resilience is cost-effective: flood defences, early warning systems, and nature-based solutions do not only reduce losses and relieve public financial burdens (e.g., UK flood defences avert an estimated GBP 1.15 billion in annual property damage), they also make insurance more available and affordable, easing strains on households and firms.

Moreover, large infrastructure investments such as the UK Thames Barrier and Dutch dike systems can deliver a so-called ‘triple dividend of resilience’: 1. Saving lives and reducing losses; 2. Supporting economic vitality by making areas more investable; and 3. Creating social and environmental co-benefits, particularly when using nature-based solutions (e.g. urban greening for heat, wetlands and beach restoration for floods).127

A comprehensive, effective resilience strategy depends on collaboration between the public and private sectors. Public investment alone cannot cover all risks. Private capacity, however, needs the right enabling conditions. Governments can align commercial incentives with national resilience ambitions.128 Public-private partnerships help pool resources and expertise, while instruments such as ILS and community-based insurance can both incentivise risk reduction and protect vulnerable populations.129

A comprehensive approach links three functions: risk assessment, risk reduction, and risk transfer. Robust risk knowledge (data, modelling) guides targeted investment and policy.130 It allows matching the right tool – risk reduction, retention, or transfer – to each risk layer, from frequent to catastrophic, in the most cost-effective way. Combining flood defences with insurance both prevents damage and supports rapid recovery.131

Public investment must be forward-looking and adaptive, recognising changing climate signals and potential tipping points. It must also acknowledge that, in some regions and for some perils, relocation or managed retreat may be necessary. Scaling finance will require instruments such as blended public-private funding or ILS. Risk-transfer pooled solutions can also enable mitigation, as seen in Flood Re’s ‘Build Back Better’ initiative and the North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association’s USD 600 million resilience bond (2025).

Despite clear benefits, many regions still rely on incremental upgrades and crisis responses that lag escalating risks. Public policy should prioritise prevention and preparedness, integrating major protective works with ecosystem-based solutions and stronger codes and land-use planning to deliver durable resilience.132

Sources: Swenja Surminski, Managing Director, Climate and Sustainability at Marsh McLennan, and Professor in Practice at the London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom

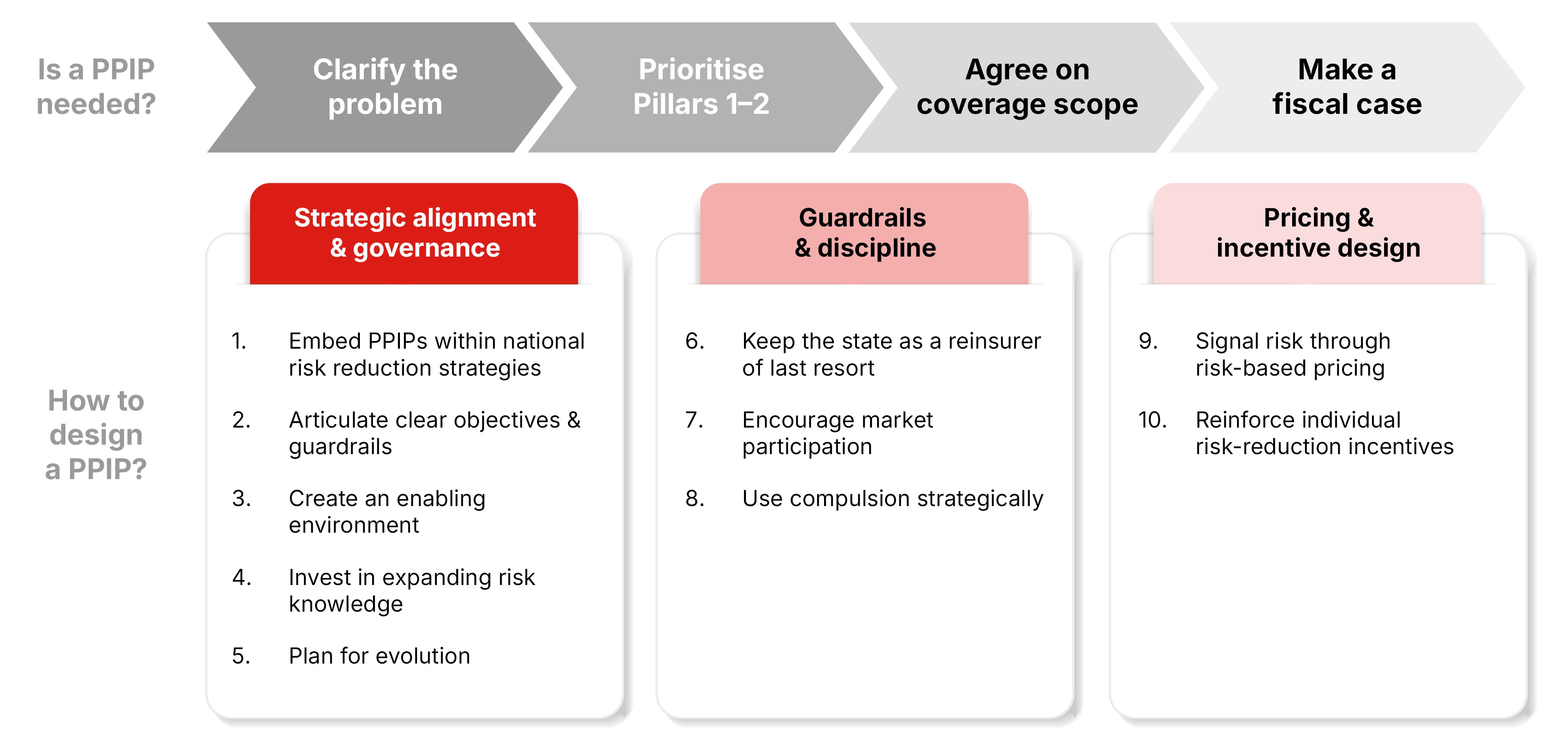

We first address the rationale for launching a PPIP. While most existing schemes were emergency responses to disasters, jurisdictions are increasingly considering this option proactively, enabling a more deliberate, less reactive approach. In all cases, launching a PPIP requires political leadership and broad stakeholder agreement on the need for intervention. Four steps can guide the process of building this consensus:

Step 1

Clarify the problem. Key stakeholders need a common, data-driven, and granular understanding of the underlying risks, the causes and consequences of protection gaps, and whether the issue is temporary or permanent.133

Step 2

Prioritise Pillars 1 and 2.134 This step minimises the residual risk that requires public-private risk-sharing (Pillar 3). Risk reduction (Pillar 1) is economically justified whenever it is more cost-effective than additional risk transfer. Market-enhancement measures (Pillar 2) are likely to cause fewer market distortions than a PPIP. For intractable risks – too catastrophic to be fully reduced or absorbed by private markets – a PPIP may be needed. PPIPs can also give policymakers time to implement necessary measures that require time to mature fully.135 Then, holding governments accountable for progress could ensure the PPIP does not delay essential Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 measures.

Step 3

Agree on the perils and exposures covered. A PPIP’s coverage should extend to vulnerable groups, such as SMEs and low-income households, and possibly to business interruption. Residual protection gaps must be acknowledged and societally acceptable.

Step 4

Quantify the fiscal case for a PPIP. A PPIP formalises a hidden fiscal liability that governments can monetise by charging the PPIP for state backing. Additionally, a state guarantee can encourage private capital accumulation, thus lowering uninsured losses. Scenario analysis can identify fiscal exposure, both with and without a PPIP.136 Forward-looking models predict how stress points may shift. Anticipating a potential winding down of the PPIP, once Pillars 1 and 2 measures are fully implemented, can help ensure fiscal exposure does not become permanent.137

A new social contract is required to redefine the role of PPIPs for resilience. Based on the comparative analysis of fourteen schemes in Sections 5 and 6, we propose 10 principles for policymakers:

Strategic alignment and governance

Principle 1

Embed PPIPs within national risk reduction strategies. PPIPs cannot succeed in isolation and must complement – not substitute for – robust public investments in risk-reduction of infrastructure, resilient building codes, effective land-use planning, and potential relocation.

Principle 2

Articulate clear objectives and guardrails. Clearly define the PPIP’s specific goals – such as improving availability, affordability, or uptake – and explicitly pair them with fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails, acknowledging inherent trade-offs.

Principle 3

Create an enabling environment. Foster legitimacy and effectiveness through early engagement with re/insurers, regulators, and consumer groups; strong coordination across national and local government; and clear regulations defining roles, governance, and oversight procedures.138 In particular, the PPIP’s operations should be insulated from short-term political deadlock.

Principle 4

Invest in expanding risk knowledge. Leverage the PPIP’s position to generate, aggregate, and share risk data and models, enhancing understanding and awareness across society and informing public policy, land-use planning, and mitigation efforts (see Box 7).

Principle 5

Plan for evolution. Design the PPIP with mechanisms for adaptation, allowing adjustments to scope, triggers, pricing, and financing structures in response to changing risks and market conditions, using performance milestones rather than fixed dates for transitions or exits.139

Guardrails and discipline

Principle 6

Keep the state as a reinsurer of last resort. Ensure state guarantees and PPIP’s own capital cover only the most catastrophic loss layers where private capacity is truly insufficient, thus minimising fiscal risk.

Principle 7

Encourage market participation. Calibrate triggers and structure re/insurance layers so private markets absorb as much risk as they sustainably can. For backstops and reinsurer-PPIPs, predictable triggers bring certainty, attracting more private insurance capacity.

Principle 8

Use compulsion strategically. When the main goal is to stabilise the market or provide additional capacity, voluntary participation preserves market discipline and competition. Compulsion should be used only when the goal is to rapidly expand coverage.

Pricing and incentives

Principle 9

Signal risk through risk-based pricing. Adopt risk-based pricing as the default to signal risk and incentivise mitigation, addressing affordability concerns through targeted, transparent subsidies rather than distorting price signals. Solidarity pricing aimed at supporting vulnerable groups should be transparent to beneficiaries and, where feasible, temporary.

Principle 10

Reinforce individual risk-reduction incentives. Use PPIP contract features and financial incentives to reward policyholders for making safer choices beyond the minimum standards. Incentives must be strong enough to change behaviour and lead to a meaningful reduction in risk. Importantly, schemes that depend on solidarity pricing need specific measures to restore lost risk-reduction incentives.

Box 7: Risk modelling, data, and insurance: resilience enablers

Open, probabilistic modelling, paired with standardised metrics and cross-sector collaboration, turns climate risk data into an enabler of resilience.

First, open access widens use and levels the field. Most models are proprietary and commercially restricted, limiting adoption in low- and middle-income countries. Open-source platforms such as CLIMADA and Oasis LMF provide free, event-based probabilistic modelling that broadens access and enables consistent analyses across users.140

Second, standardised methods turn data into actionable, comparable signals. Disclosure of physical climate risk is expanding, but varied, incomparable metrics prevent portfolio-level aggregation and obscure systemic vulnerabilities. Adopting standardised, event-based probabilistic assessments unifies metrics, directs capital toward firms better equipped to manage climate impacts, and incentivises corporate adaptation, strengthening systemic resilience.

Third, risk-pooling benefits from model-driven design, especially at a global scale. Many catastrophe pools and PPIPs operate regionally without maximising diversification. Modelling shows that global pooling can improve diversification by up to 65% versus regional designs. Probabilistic optimisation of pool composition reduces the cost of climate impacts while improving liquidity access.

Fourth, insurance translates modelling into incentives and protection. Using probabilistic tools, insurers price climate risk more accurately and design products that align financial incentives with resilience outcomes. Premium discounts for risk reduction, parametric covers that rapidly deliver liquidity, and index-based schemes for small farms illustrate how modelling can drive behavioural change while providing financial protection.

Collaboration is the operating system of resilience. Open tools link climate science to decision-making by quantifying impacts, evaluating risk reduction and transfer options, and assessing cost–benefit trade-offs. Scientists deliver methodologies and hazard data. Policymakers create enabling regulations. Financial institutions design risk transfer mechanisms. Finally, businesses implement adaptation measures to safeguard assets and operations. While no single actor can tackle climate risks alone, an integrated ecosystem that relies on data-driven modelling, financial innovation, and cross-sector collaboration offers a pathway to building a more resilient future.

Source: David Bresch, Professor for Weather and Climate Risks, ETH Zürich, Switzerland

Figure 12 summarises these policy recommendations.

Figure 12: Policy recommendations: four steps and ten principles

Source: Geneva Association

Cyber risk and pandemic business interruption (BI) are often cited as candidates for future PPIPs. Both involve highly systemic, hard-to-model losses and large protection gaps. Applying the four-step framework in Section 7.1 shows that the case for PPIPs differs across the two perils.

For cyber, there may be a role for a PPIP focused on extreme, systemic events, but design is complex and political momentum is limited. For pandemic BI, the risk is essentially fiscal rather than insurable in a traditional sense. A PPIP could provide a short-term liquidity bridge for some businesses within a broader public health and fiscal strategy.

7.3.1 Addressing the cyber protection gap

Cyber risk is now a major threat to economic stability, driven by global digitalisation, the concentration of a few critical service providers, and increasingly hostile nation-state activity. Global losses are estimated at trillions of US dollars, most of which would be uninsured.141 Several governments and industry bodies in the US, UK and EU have explored the use of PPIPs for extreme, systemic cyber events, often inspired by terrorism programmes.

Step 1: Clarify the problem

Cyber threats and exposures evolve quickly, so historical data is sparse and only weakly predictive, while mitigation measures lag new attack methods. Insurers respond with aggregate caps (limits on total payouts across all claims in a year) and sub-limits (limits on specific loss types within a policy), and by excluding un-modellable events such as cyber war and critical infrastructure outages.142 At the same time, demand for cyber insurance, especially from SMEs, remains limited due to low awareness, affordability constraints, product complexity and failure to meet cybersecurity standards.143 Recent market growth has fallen short of previous expectations.144

This pattern differs from natural disasters and terrorism. There has been no major shock event triggering wholesale capacity withdrawal, as after 9/11 attacks, nor recurring public relief costs comparable to earthquakes or floods. Fear of a future catastrophe constrains insurance growth, but premiums are currently softening. The cyber protection gap thus reflects three drivers: rising threats and lagging mitigation; low adoption, especially among SMEs; and limited insurance capacity for tail risks, including excluded events such as cyber war.

Step 2: Prioritise Pillars 1 and 2

The priority for governments is to strengthen Pillar 1 by raising baseline cyber hygiene. This includes national frameworks and standards, sectoral regulation for critical infrastructure, and incentives or requirements for basic controls such as secure configurations and incident response plans.145

Pillar 2 focuses on enabling private cyber insurance markets. Key measures include better incident reporting, more standardised policy terms and knowledge sharing to improve modelling. Targeted mandates, tax incentives and awareness campaigns can stimulate demand, especially from SMEs. Where insurers link cover and pricing to cybersecurity standards, higher cyber insurance uptake can also support national resilience objectives.146

These measures may eventually support risk transfer to capital markets via ILS, adding capacity for tail risk.147 However, fast-evolving threats mean that residual uncertainty – ‘unknowable unknowns’ – will likely remain, limiting private appetite for the most extreme layers.148

Step 3: Agree on the perils and exposures covered

Proposals for cyber PPIPs target different parts of the protection gap. To address the shortage of capacity for catastrophic events, some suggest a market-stabiliser PPIP:

A reinsurer-PPIP or backstop with clear liability limits and a state guarantee could encourage insurers to offer broader cover and higher limits, potentially increasing coverage value and uptake.151

Several proposals focus on SMEs because of their vulnerability and position as potential entry points into supply chains.152 These include the financing of SME compensation through levies on cyber-adjacent property and casualty lines.153

Step 4: Quantify the fiscal case for a PPIP

Cyber catastrophe models are relatively new and produce divergent loss estimates.154 This complicates the assessment of potential economic losses and fiscal exposure. Nonetheless, a major cyber catastrophe would likely require public support, indicating that states already bear an implicit risk.155 A PPIP could help monetise this implicit liability.156 However, this presents a technical challenge: determining an accurate price for a state guarantee covering events that are difficult or impossible to model. Some proposals, therefore, rely on post-event recoupment, as under TRIP (US).157

Design principles for a cyber PPIP

If a cyber PPIP is introduced, the design principles in Section 7.1 must be adapted to the nature of cyber risk. This presents potential challenges:

Overall, there is a clear theoretical case for a PPIP to provide capacity for large-scale, uncertain and ambiguous cyber losses. Such an intervention could support the growth of the cyber insurance market. Still, design is complex and political momentum is limited, especially in a context of high public debt. History suggests that such interventions usually gain traction only after a crisis.

7.3.2 Address the pandemic business interruption protection gap

Business interruption (BI) losses are a foremost corporate concern, second only to cyber risk.166 The pandemic revealed a significant protection gap as most BI losses caused by the virus and related government measures went uninsured. This has sparked interest in ex-ante financing mechanisms, including PPIPs, to enhance resilience against future pandemics.167

Step 1: Clarify the problem

Pandemic BI poses an even greater insurability challenge than cyber.168 Losses are highly interconnected across sectors and regions, driven by government mandates such as lockdowns and social distancing. Pathogen behaviour, policy responses, and supply-chain disruptions add further uncertainty. During COVID-19, BI losses in the United States alone were estimated at around USD 1 trillion per month; if insured, claims from small businesses could have depleted the capital of the entire US property and casualty sector within a few months.169

Most BI policies now exclude pandemic losses entirely. Before COVID-19, demand for pandemic BI cover was negligible; afterwards, capacity tightened further, and public support in many countries reduced the perceived need for insurance.170 Supply and demand for pandemic BI would thus need to be built almost from scratch.

Step 2: Prioritise Pillars 1 and 2

To lessen the impacts of the pandemic on life, health, and the economy (Pillar 1), governments depend on surveillance, early warning systems, public health measures, and preparedness, including vaccine research and rapid approval pathways. Businesses can diversify suppliers, adjust inventories, improve ventilation and remote working capabilities, and enhance continuity plans.171 Grants, tax incentives, and regulatory standards can promote such adaptations.172,173

Pillar 2 seeks to improve the terms under which private BI insurance markets, where they exist, operate. Products would need clear, simple triggers, shorter indemnity periods or higher deductibles, and better data to support modelling.174 ILS or multi-year and multi-line policies might provide additional, diversified capacity. 175 Even with such a redesign, however, systemic tail risk will likely remain beyond insurers’ risk-absorbing capacity.

Step 3: Agree on the perils and exposures covered

Given SMEs’ vulnerability, many proposals focus on them, sometimes incorporating compulsory elements inspired by coverage-expander PPIPs for natural catastrophes. Larger firms would be handled through more market-oriented solutions, including risk-based pricing, risk mitigation, and voluntary participation, with a state-backed reinsurer-PPIP to provide additional risk-absorbing capacity.

To balance affordability and fiscal prudence, proposals generally favour limited, time-bound support rather than full indemnity of BI losses. As with capped earthquake cover in programmes such as NHC (New Zealand) or TCIP (Türkiye), pandemic PPIPs would provide liquidity for a set period (e.g. three months), with governments responsible for longer-term relief.176 The aim is to ensure business continuity at the lowest possible cost.

Step 4: Quantify the fiscal case for a PPIP

Given the scale of potential losses, insurers would probably cover only a small part of a pandemic BI PPIP. Proposals typically envisage private contributions ranging from 0–5%, possibly increasing to around 10% after two decades of capital accumulation.177 The main guardrail to consider is therefore fiscal: any PPIP would mainly formalise and cover potential costs in advance that taxpayers would otherwise bear after the fact. The rationale for such a PPIP is therefore not traditional risk sharing, but:

Governments may hesitate to commit to substantial state guarantees, especially when a PPIP would not eliminate the need for ad hoc measures and when benefits from rare events must be balanced against fixed administrative costs.179 These concerns challenge both fiscal and operational guardrails.

In summary, a pandemic BI PPIP could help maintain continuity for SMEs and vulnerable groups but is unlikely to replace large-scale public intervention. It would be, at best, one component of a much broader health and economic resilience strategy.

Globally, disaster risk is accelerating faster than societies can adapt, widening protection gaps and testing the limits of re/insurance markets. The industry now faces a defining question: how to preserve insurability in a world where risk is growing and becoming increasingly systemic.

This report analyses the traditional role of PPIPs as powerful risk-sharing mechanisms. Our analysis of fourteen schemes demonstrates their ability to stabilise markets and expand coverage. However, it also shows that their design is a complex balancing act, navigating difficult trade-offs between fiscal, market, social, and operational guardrails.